Back in September, I wrote a piece that highlighted a notable but underestimated accomplishment in Chicago’s housing market. The 2023 U.S. Census’ American Community Survey data showed that Chicago reached its highest number of occupied dwelling units, 1.18 million, surpassing its previous high mark of 1.16 million in 1960.

On the surface this seems like an unremarkable feat. Yet this single data point might tell us more about the impact of demographic change in cities, and how such change alters their social and economic profiles, than anything. More from that article:

“The number of occupied dwelling units in Chicago hit bottom in 1990, with 1.03 million. Since then Chicago’s been adding about 4,500 occupied units annually, or about 0.4% each year.

It’s modest but meaningful change. It’s actual growth, really, especially considering that Chicago’s population dropped by 900,000 between 1960 and 1990, and an additional 150,000 since 1990. As Hertz says in the post, “(i)n other words, >100% of the population decline of the city is now explained by (decreasing) household size.””

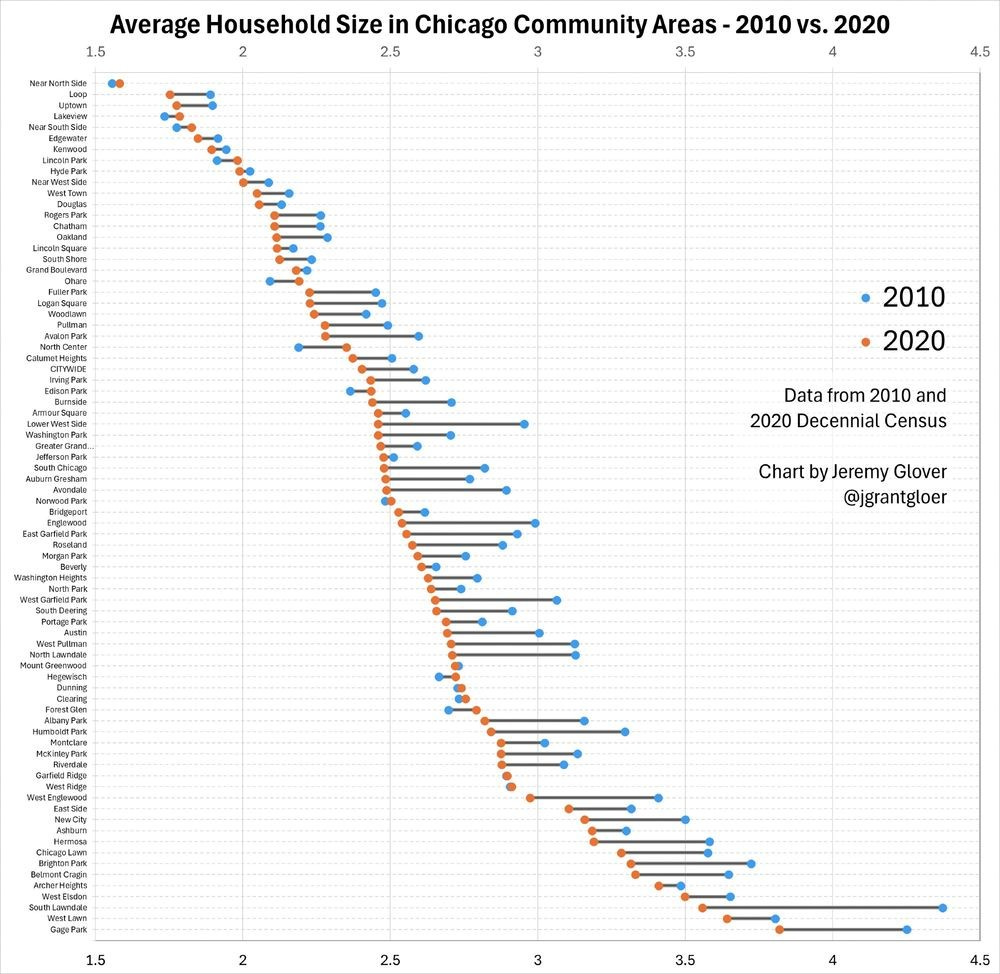

You can see how much average household size decreased in Chicago in this chart produced by Jeremy Glover (@jgrantglover.bsky.social) and published at Blue Sky. With his permission (thanks!) I’m showing his chart here:

Between 2010 and 2020, 63 of Chicago’s 77 Community Areas (groups of neighborhoods that Chicago’s kept statistical tabs on for more than a century) saw a decrease in average household size. Of the 14 Community Areas that did witness an increase in average household size, eight were among the highest valued and/or lowest average household size Community Areas in the city). The other six were likely the benefactors of Latino migration from inner Chicago neighborhoods to areas closer to the city’s boundaries. Elsewhere, average household size keeps falling.

Chicago’s population has been virtually flat since 1990, but the number of occupied dwelling units is increasing. That got me thinking: how much of our nation’s housing crisis – our outright housing shortage – can be attributed to decreasing household size?

My guess is far more than most urban observers recognize.

I touched on this point in a series I started earlier this year, and republished just last month. In it I spoke of unconventional causes of the housing crisis.

Read the rest of this piece at The Corner Side Yard.

Pete Saunders is a writer and researcher whose work focuses on urbanism and public policy. Pete has been the editor/publisher of the Corner Side Yard, an urbanist blog, since 2012. Pete is also an urban affairs contributor to Forbes Magazine's online platform. Pete's writings have been published widely in traditional and internet media outlets, including the feature article in the December 2018 issue of Planning Magazine. Pete has more than twenty years' experience in planning, economic development, and community development, with stops in the public, private and non-profit sectors. He lives in Chicago.

Photo: Volker Thimm via Pexels, in Public Domain.

willing landlords

A higher % of occupancy, if accurate, reflects less withholding of units from the market. Some good news from Chicago! In NYC, with its rent controls and other anti-landlord rules, increasing numbers of apartments are banked.