Vancouver is consistently rated among the most desirable places to live in the Economist’s annual ranking of cities. In fact, this year it topped the list. Of course, it also topped another list. Vancouver was ranked as the city with the most unaffordable housing in the English speaking world by Demographia’s annual survey. According to the survey criteria, housing prices in an affordable market should have an “median multiple” of no higher than 3.0 (meaning that median housing price should cost no more than 3 times the median annual gross household income). Vancouver came in at a staggering 9.3. The second most expensive major Canadian city, Toronto, has an index of only 5.2. Even legendarily unaffordable London and New York were significantly lower, coming in at 7.1 and 7.0 respectively. While there are many factors that make Vancouver a naturally expensive market, there are a number of land use regulations that contribute to the high housing costs.

Vancouver is a unique real estate market: it’s the only major Canadian city that doesn’t experience frigid winters. This makes it a major draw for high skilled, high salary employees. It is also a major destination for wealthy Canadian retirees, who choose to actually spend their winters in Canada. There is little doubt that it is a naturally expensive real estate market. As with coastal California cities, people pay a premium for (in this case relatively) hospitable weather. The proximity to world class skiing, fishing, and hiking are no doubt another factor in the city’s high real estate costs. There is certainly a premium to be paid for living less than two hours away from the world’s best ski resort.

Moreover, Vancouver has become an appealing real estate market for overseas investors, particularly Chinese nationals. There has been a good deal of news recently about how many of the nouveau riche in China are now looking to Vancouver, rather than Los Angeles or New York as an immigration destination. In absolute dollar terms, Vancouver is still cheaper than either city. This, combined with the more hospitable Canadian immigration system, has made Vancouver so attractive to overseas investors that real estate agents are now organizing house hunting tours for potential Chinese buyers.

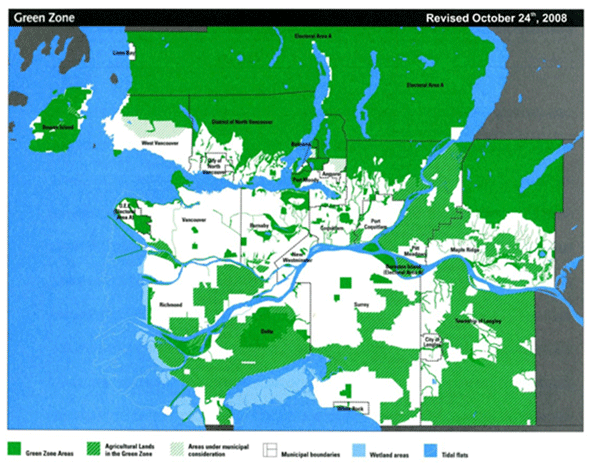

To be sure, geography deserves much of the blame for Vancouver’s high housing costs. But a large chunk of the blame lies with restrictive municipal and provincial land use policies. Since the introduction of the city’s first comprehensive plan in 1929, Vancouver has used various land use regulations to create dense mixed use development in order to protect green space surrounding the city. In 1972, the provincial government passed legislation aimed at protecting BC farmland. This left less than half of the already scarce land in Greater Vancouver off limits to developers. As a result, the city is circled by undeveloped land, referred to as the Green Zone. The Green Zone acts as a de facto urban growth boundary, largely designed to prevent sprawl.

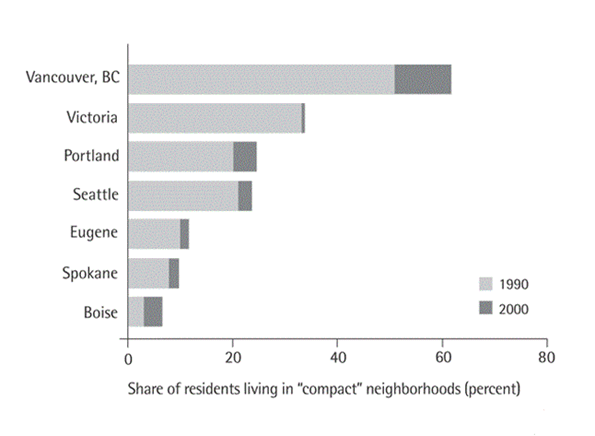

As a result, Vancouver is one of the few North American cities that have been growing almost exclusively upwards, rather than outwards for the last century. Its narrow streets and lack of a major highway running through the city make it one of the least automobile friendly cities on the continent. Unsurprisingly, Vancouver was ranked the most smart growth oriented city in the Pacific Northwest by the Sightline Institute. Roughly three times more Vancouver residents live in compact neighborhoods as a percentage of the population compared than Portland or Seattle. This arguably makes Vancouver the most smart growth oriented city in North America.

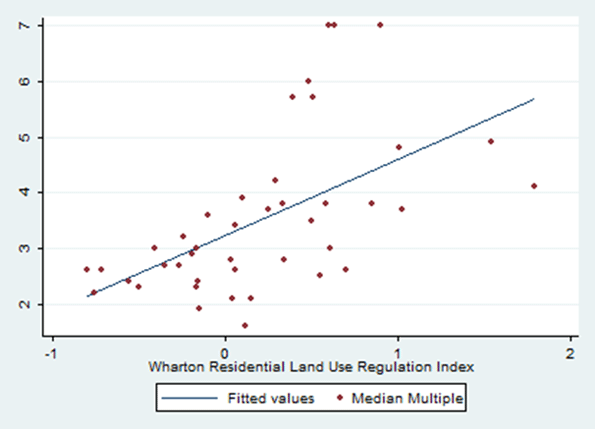

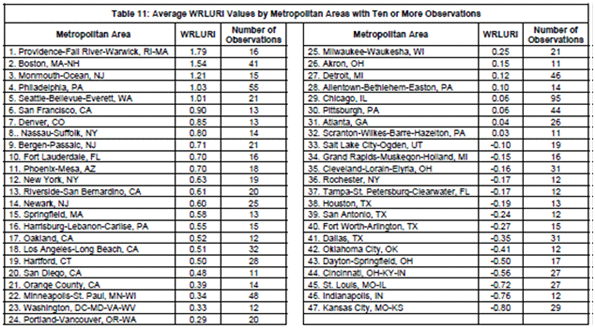

Smart growth has become a truism for urban planners. Walkable communities with a mix of commercial and residential units combined with strict zoning regulations to encourage transit usage is a formula increasingly prescribed for North American cities. Though many smart growth principles are attractive, there is an strong correlation between heavy land use regulations and housing costs. Using data from the Wharton Residential Land Use Regulation Index (WRLURI), and Demographia’s International Housing Affordability Survey, a simple scatter plot diagram has been included to illustrate this correlation.

The WRLURI measures the stringency of land use controls imposed on various US jurisdictions by state and local governments. There is a clear correlation between high regulations, and low housing affordability. Though the index does not include Canadian cities, it does include neighboring Seattle. Seattle ranks fifth of 47 cities on the Wharton Index. According to a recent study in Boston College International & Comparative Law Review by David Fox, Vancouver is decades ahead of Seattle in terms of smart growth policies. This means that Vancouver would rank at least fifth in North America on the index, though it is more realistic to assume it would most certainly top the index.

In addition to smart growth policies, Vancouver also has very stringent inclusionary zoning laws. Inclusionary zoning requires developers to provide a certain number of affordable housing units in any given development. This policy might seem to make the city more affordable, but it functions exactly like rent control. Those fortunate enough to find spaces in the affordable housing units pay less, but the subsidized rent is made up for by higher rent in adjacent units. In a study of inclusionary zoning in California cities, Benjamin Powell and Edward Stringham from the Department of Economics at San Jose State University found that inclusionary zoning imposes an additional $33,000-$66,000 cost on adjacent market rate units.

There have been some recent policy initiatives that may reduce the cost of housing marginally. In 2004, the city amended its zoning code to permit secondary suites throughout the city. Secondary suites are subdivided units of owner occupied homes that are used as rental units. This zoning change brought tens of thousands of relatively low cost units into the market. There are currently 120,000 secondary suites in the province. The city recently went one step further to allow homeowners to convert laneway garages into rental units. These units have a maximum of 500 square feet. There are 70,000 homes in Vancouver that are eligible for conversion, though it is unclear how many will take up the offer. This will add to the stock of relatively affordable rental housing in the city, but may not significantly reduce housing costs. In fact, by increasing the revenue generating potential of houses, it may actually increase the cost of purchasing a single dwelling home. After all, if the potential rental income of a single dwelling unit increases, the market price of the unit is likely to do the same. This isn’t necessarily an argument against the policy, though it does underscore the fact that housing costs in Vancouver will never decrease without liberalizing municipal and provincial land use policies.

In short, the City of Vancouver and Province of British Columbia have chosen to favor compact growth over affordable housing costs. This likely makes the city more attractive to affluents from both the rest of Canada and abroad, but increasingly makes it unaffordable for middle class families. There is certainly some substance to the Economist’s claim that Vancouver is the most livable city on earth. It is a very attractive place for those who can afford it. Nevertheless, creating a city fit only for the wealthiest segments of society and non-families is hardly something to be proud of.

Downtown Vancouver photo by runningclouds

Steve Lafleur is a public policy analyst and political consultant based out of Calgary, Alberta. For more detail, see his blog.

Nice post. I was checking

Nice post. I was checking constantly this blog and I am impressed! Extremely helpful information specially the last part I care for such info a lot. I was seeking this particular information for a very long time. Thank you and good luck.

what is conversational hypnosis

Wonderful

_____________________________

Great sharing

______________________________

The city recently went one

The city recently went one step further to allow homeowners to convert laneway garages into rental units. These units have a maximum of 500 square feet. There are 70,000 homes in Vancouver that are eligible for conversion, though it is unclear how many will take up the offer. OTC Sleep Aids

The Big Picture

Restricting urban sprawl might result in apparent improvement in some carefully selected factors, and some encouraging anecdotal evidence. But in the long term, here is why it is doomed to failure.

1) Land prices are driven up to such an extent that increasing proportions of the population ultimately cannot afford to live anywhere, (and take on subprime mortgage debt as the only means of coping); but especially not in costlier convenient locations where the planners hoped they would live. Land is demonstrably driven up 20 times, 50 times, and more, in "value". The fact that inner area land is a "factor" higher in price than fringe land, means that 7-figure lots become the norm in the inner area. This REMOVES the "choice" of living in these areas for MOST people.

2) Congestion is increased simply because the greater majority of people still use cars to travel, even if they live at higher densities. Manhattan has one of the highest rates of public transport use in the world, yet they still have far more "vehicle trips" per square mile than any other city. Adding people ALWAYS ADDS vehicle trips to the total, it NEVER subtracts them.

3) The cost of upgrading old infrastructure to cope with the increased numbers of people, is very much higher because of the need for massive disruption of existing activity, and complex access problems for the engineers. Greenfields is actually much cheaper. (It is cheap to build "walkable" "edge cities", but it is prohibitively expensive to buy a home in an inner area walkable community where all land values have been forced up by urban planning).

4) These effects, cumulatively, but especially the "bubble" consequences of land price escalation; can easily be observed today destroying city economies all over the OECD - while the only economic bright spots are in the remaining areas of the USA (God bless 'em) that still have NOT succumbed to the worst ideas of "smart growth". Perhaps much of Canada too, although Vancouver is Smart Growth's new bubble poster child now that all the US bubbles have burst.

There is also a very strong intergenerational equity issue and a very strong social mobility issue. It is deeply ironic that leftwing politicians and activists who claim to care about poorer people and the young, are the most guilty of depriving these people of housing options and placing them under unprecedented financial stress. This certainly includes the cost of longer commutes than they would have had if land values had remained cheap enough for them to locate conveniently rather than according to "Hobson's Choice" "most affordable" - but still severely unaffordable by historical standards - "choices".

It is all very well for smarter buyers to wait for a periodic crash in which to buy their first home, but the problem is that these periodic crashes will be accompanied by recession and unemployment and tightened credit. By the way, Britain, since its Town and Country Planning Act in 1947, is a working illustration of this cycle, which has happened every 12 to 16 years for decades now.

It is a question whether the world economy can stand this happening again and again in the entire OECD simultaneously, as the OECD states in a recent report "A Bird's-Eye View of OECD Housing Markets". Most of the OECD nations have had simultaneous housing bubbles this time around. Blaming it on Wall Street/Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac/Alan Greenspan/Tax laws etc etc etc just does not work. This was "the urban planners housing bubble" - they just haven't been made to wear it yet.

Cognitive dissonance runs rampant on this site

Vancouver's home prices are high. Yes, they are indeed. It's called the free market. Yes, the free market, that these corporate libertarians kneel and pray to. People WANT to live in places like Vancouver, when that happens, prices go up. It has always been fun to read this site, with the level of cognitive dissonance that the authors must have. It seems that they can blame just about everything on government planning. Mumps? that's government. Locust infestation? that's big government for you.

Are you familiar with Cognitive Dissonance? Perhaps the authors of this site should look it up, and get some serious therapy. Just make sure it's not a therapist that takes big government subsidies, or took government subsidies to get their education.

This is a very traditional

This is a very traditional newgeography.com editorial, pro-suburbia and pro-sprawl all the way. Some elements of its analysis are correct, but it has some glaring errors, huge simplifications and unrealistic solutions to solving Vancouver's problem with housing affordability.

First, Metro Vancouver's geography is even more compact than that map suggests. The areas that say "Green Zone" without the white diagonal lines are almost exclusively major parks or Mountains. If someone were to propose that Central Park in New York be redeveloped to improve affordability in Manhattan would that be a realistic proposal? So why would it be realistic to "liberalize" land use policies as it pertains to Stanley Park, Queen Elizabeth Park, Pacific Spirit Park, Burns Bog or Burnaby Mountain (just to name a few?) As for the latter, one can't physically build a lot of housing on a mountain range, which covers the entire area northern third of that map. Again, it's not even possible to liberalize that aspect of land use policies.

It's true that the ALR could be opened up to development, but that leads to the question as to why existing low-density areas couldn't have their density be increased? At the very least that would save on infrastructure costs. Beside those costs, there are additional ones in transportation, health and environmental degradation that go along with unchecked sprawl. Do they offset increased housing costs? Not to mention the fact that this ALR land is some of the most productive farmland in a province with little of it.

The last point is political, but that leads to something that's a more realistic solution to Vancouver's affordability problems. The editorial did a pretty weak job of addressing this. I believe this is the only realistic way to solving this problem. Most Metro Vancouver governments haven't had the will to implement serious affordable housing policies, because said policies aren't in their political interests or home owners financial interests. If it isn't in the latter's interests, they won't vote for the former. The housing industry in Vancouver is very important to the financial well being of home owners in Vancouver, thus any proposal to say tax non-resident investment/holiday properties (that sit un-used most of the year) and direct that to affordable housing or subsidized housing aren't seriously perused. Existing home owners like the fact that their properties values have increased substantially and will oppose any attempts to change this. Until municipal politicians are willing to risk the political backlash, and until higher levels of government are willing to help them with money to do this, attempts to build affordable housing will be severely hampered. Yes this will require "liberalized land use policies" to some degree. But I disagree that it has to be at the cost of parkland, or agricultural areas.

Furthermore you overstate government requirements for developers to include affordable housing components in projects. The last serious time this happened was in the mid 1970s when the South False Creek area between Cambie Street, 6th Ave and Granville Street was redeveloped. This lead to a neighbourhood where 1/3rd was at market rates, 1/3rd was at an affordable subsidized rate and 1/3rd was at one third of a renter's income rate. After this the political pendulum swung to the right and most developments where affordable units were included had, at best, 20% of their units designated as affordable in one of the latter two categories. Even the high-profile Woodwards project hasn't achieved such a formula. The high profile Olympic Village actually jettisoned most of its 'affordable' component to insure that it breaks even, as the City of Vancouver, without any funding from senior levels of government, had to insure its construction on time for the Olympics. The South East False Creek area, that the latter is located in, had the 1/3rd, 1/3rd and 1/3rd formula used in the South False Creek area proposed for its redevelopment back in 2002, but a new municipal administration in 2005 jettisoned that requirement.

This leads into land use policies in the region. Despite there being an extensive part of the population that lives in "high density" neighbourhoods, most of the region has the character of a traditional single-detached suburban area outside of select areas. There's always a vocal section of NIMBYs who oppose any attempts to build density, anywhere, especially outside of the Downtown area. Vancouver doesn't have a skyscraper within the top ten in Canada, despite its impressive looking downtown Skyline.

Affordable Housing

@Tessa - The City Council has already given approval for an afforable family rental complex built in the 1970's - that has 70 units at Cambie & Marine to be replaced and redeveloped. When speaking with a City staffer, he confirmed that while the units will be replaced one for one, they will not be offered back out at the same rental rate. So at the moment, there are pockets of affordable rental housing generated in the 70's, but a new standard is being set in motion that will ultimately encourage others to replace their complexes. Not a single Councillor visited the area or the complex that they were passing a motion to have replaced. Vancouver is embarking on a new era of "build first, think later" - ultimately this could be very negative for Vancouver as not enough attention is being paid to doing any of this right. Growing up in Vancouver, I quite literally never bothered to get my drivers license - I completely support the concept of walkable communities - I also own my own home and I have the security of that, but I don't support the replacement of affordable housing, without first looking to see what is actually being raplaced.

questioning land use policy

I would question the author's claim that Vancouver has a "very stringent inclusionary zoning laws". Vancouver has a 20% social housing policy, but it only applies to large sites undergoing rezoning, typically from industrial to residential, that results in the creation of new neighbourhoods. Every inclusionary zoning policies are very different, and Vancouver's 20% policy if far from what IZ looks like in the U.S.

Second the connection that the author makes between Vancouver's inclusionary policy to the study that found IZ adds $33K - $66K cost to adjacent market units is misleading. In the case of Vancouver, development sites that triggers the 20% policy are usually industrial land or other land use with very little or no residential density. The developers gains in land value as the result of increased density from rezoning. It is false to assume that the policy makes market units more expensive, when in fact, there would have been no units (and no residential value) at all without rezoning in the first place.

Upzoning plus inclusionary

Upzoning plus inclusionary zoning can lead to lower costs compared to the status quo. However, upzoning without IZ would lead to even lower costs. There is still an implicit cost to the market rate units.