Vancouver is consistently rated among the most desirable places to live in the Economist’s annual ranking of cities. In fact, this year it topped the list. Of course, it also topped another list. Vancouver was ranked as the city with the most unaffordable housing in the English speaking world by Demographia’s annual survey. According to the survey criteria, housing prices in an affordable market should have an “median multiple” of no higher than 3.0 (meaning that median housing price should cost no more than 3 times the median annual gross household income). Vancouver came in at a staggering 9.3. The second most expensive major Canadian city, Toronto, has an index of only 5.2. Even legendarily unaffordable London and New York were significantly lower, coming in at 7.1 and 7.0 respectively. While there are many factors that make Vancouver a naturally expensive market, there are a number of land use regulations that contribute to the high housing costs.

Vancouver is a unique real estate market: it’s the only major Canadian city that doesn’t experience frigid winters. This makes it a major draw for high skilled, high salary employees. It is also a major destination for wealthy Canadian retirees, who choose to actually spend their winters in Canada. There is little doubt that it is a naturally expensive real estate market. As with coastal California cities, people pay a premium for (in this case relatively) hospitable weather. The proximity to world class skiing, fishing, and hiking are no doubt another factor in the city’s high real estate costs. There is certainly a premium to be paid for living less than two hours away from the world’s best ski resort.

Moreover, Vancouver has become an appealing real estate market for overseas investors, particularly Chinese nationals. There has been a good deal of news recently about how many of the nouveau riche in China are now looking to Vancouver, rather than Los Angeles or New York as an immigration destination. In absolute dollar terms, Vancouver is still cheaper than either city. This, combined with the more hospitable Canadian immigration system, has made Vancouver so attractive to overseas investors that real estate agents are now organizing house hunting tours for potential Chinese buyers.

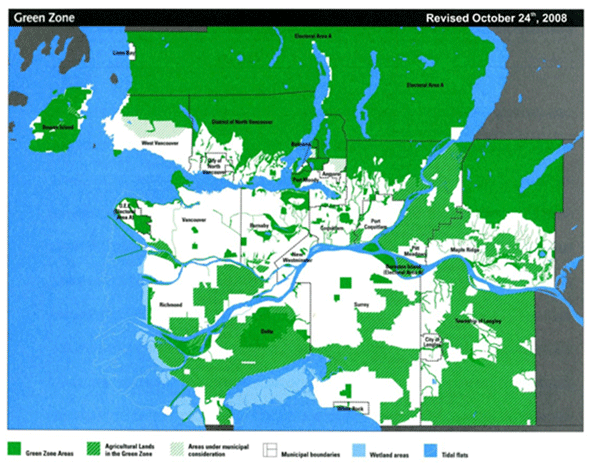

To be sure, geography deserves much of the blame for Vancouver’s high housing costs. But a large chunk of the blame lies with restrictive municipal and provincial land use policies. Since the introduction of the city’s first comprehensive plan in 1929, Vancouver has used various land use regulations to create dense mixed use development in order to protect green space surrounding the city. In 1972, the provincial government passed legislation aimed at protecting BC farmland. This left less than half of the already scarce land in Greater Vancouver off limits to developers. As a result, the city is circled by undeveloped land, referred to as the Green Zone. The Green Zone acts as a de facto urban growth boundary, largely designed to prevent sprawl.

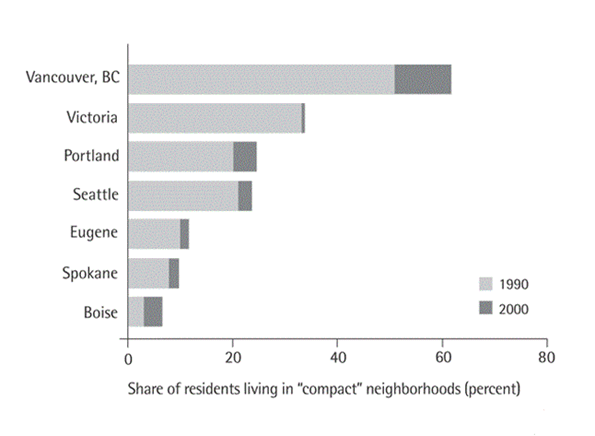

As a result, Vancouver is one of the few North American cities that have been growing almost exclusively upwards, rather than outwards for the last century. Its narrow streets and lack of a major highway running through the city make it one of the least automobile friendly cities on the continent. Unsurprisingly, Vancouver was ranked the most smart growth oriented city in the Pacific Northwest by the Sightline Institute. Roughly three times more Vancouver residents live in compact neighborhoods as a percentage of the population compared than Portland or Seattle. This arguably makes Vancouver the most smart growth oriented city in North America.

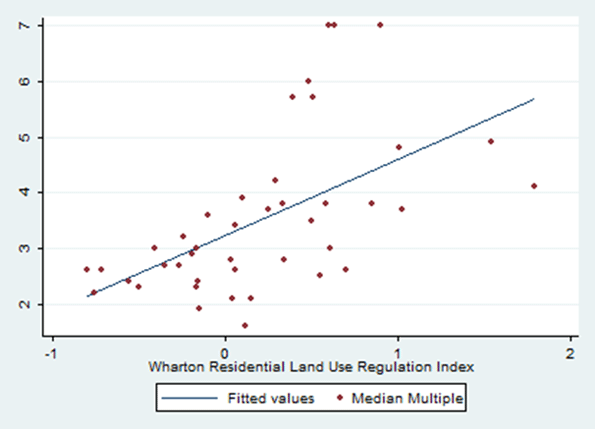

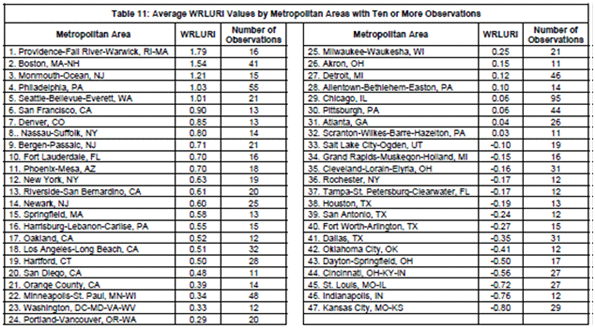

Smart growth has become a truism for urban planners. Walkable communities with a mix of commercial and residential units combined with strict zoning regulations to encourage transit usage is a formula increasingly prescribed for North American cities. Though many smart growth principles are attractive, there is an strong correlation between heavy land use regulations and housing costs. Using data from the Wharton Residential Land Use Regulation Index (WRLURI), and Demographia’s International Housing Affordability Survey, a simple scatter plot diagram has been included to illustrate this correlation.

The WRLURI measures the stringency of land use controls imposed on various US jurisdictions by state and local governments. There is a clear correlation between high regulations, and low housing affordability. Though the index does not include Canadian cities, it does include neighboring Seattle. Seattle ranks fifth of 47 cities on the Wharton Index. According to a recent study in Boston College International & Comparative Law Review by David Fox, Vancouver is decades ahead of Seattle in terms of smart growth policies. This means that Vancouver would rank at least fifth in North America on the index, though it is more realistic to assume it would most certainly top the index.

In addition to smart growth policies, Vancouver also has very stringent inclusionary zoning laws. Inclusionary zoning requires developers to provide a certain number of affordable housing units in any given development. This policy might seem to make the city more affordable, but it functions exactly like rent control. Those fortunate enough to find spaces in the affordable housing units pay less, but the subsidized rent is made up for by higher rent in adjacent units. In a study of inclusionary zoning in California cities, Benjamin Powell and Edward Stringham from the Department of Economics at San Jose State University found that inclusionary zoning imposes an additional $33,000-$66,000 cost on adjacent market rate units.

There have been some recent policy initiatives that may reduce the cost of housing marginally. In 2004, the city amended its zoning code to permit secondary suites throughout the city. Secondary suites are subdivided units of owner occupied homes that are used as rental units. This zoning change brought tens of thousands of relatively low cost units into the market. There are currently 120,000 secondary suites in the province. The city recently went one step further to allow homeowners to convert laneway garages into rental units. These units have a maximum of 500 square feet. There are 70,000 homes in Vancouver that are eligible for conversion, though it is unclear how many will take up the offer. This will add to the stock of relatively affordable rental housing in the city, but may not significantly reduce housing costs. In fact, by increasing the revenue generating potential of houses, it may actually increase the cost of purchasing a single dwelling home. After all, if the potential rental income of a single dwelling unit increases, the market price of the unit is likely to do the same. This isn’t necessarily an argument against the policy, though it does underscore the fact that housing costs in Vancouver will never decrease without liberalizing municipal and provincial land use policies.

In short, the City of Vancouver and Province of British Columbia have chosen to favor compact growth over affordable housing costs. This likely makes the city more attractive to affluents from both the rest of Canada and abroad, but increasingly makes it unaffordable for middle class families. There is certainly some substance to the Economist’s claim that Vancouver is the most livable city on earth. It is a very attractive place for those who can afford it. Nevertheless, creating a city fit only for the wealthiest segments of society and non-families is hardly something to be proud of.

Downtown Vancouver photo by runningclouds

Steve Lafleur is a public policy analyst and political consultant based out of Calgary, Alberta. For more detail, see his blog.

A co,uple points on affordability

The author speaks of the Agricultural Land Reserve and policies to create density as something that drives up unaffordability, but I think that misses the mark. The ALR creates dense, walkable neighbourhoods, to the point where most people don't need to own a car. That saves an amazing amount of money: $1000 or so for annual insurance costs, and for a new car you're talking a lease of likely at least $3,000 a year, or similar costs if you're paying via financing. That's not even mentioning gas. Really, it's the overall cost of living that we ought to be measuring, not just housing, as it doesn't tell the whole story.

Also, you talk a lot about "liberalizing" (eliminating) land use controls, but you don't once mention that the vast majority of land in Vancouver and the suburbs are zoned single family residential, which prevents anyone from densifying those neighbourhoods into much more urban development. If you simply rezoned those areas to allow for a much wider variety of development, ranging from single family homes with secondary suites to low and mid-rise apartments, the affordability problem would likely disappear relatively quickly, and we still would be able to save money in other areas such as transportation.

We could also focus on so-called third tier housing, something that is not exactly homeowner or rental, but areas where the city owns the land and you lease the property (as is done in False Creek South), or non-profit housing providers. Vancouver has a huge number of cooperative housing buildings that were built largely in the 70's, and are still some of the most affordable housing in the city.

I agree that Vancouver has a housing crisis, a very serious one, but abandoning density and the ALR for urban sprawl throughout the valley isn't going to solve the problem, and it certainly isn't going to keep the region as somewhere that's worth living.

Housing Crisis

Firstly, Tessa, see my comment below about "Density Profiles and Social Justice". High land costs DEPRIVE low income earners of the choice of trading off mileage and mortgage payments - they don't ENABLE this choice.

You can see that Vancouver has a serious housing crisis. If you want to know what are the logical conclusions of your planning preferences, take a look at England, where they have been in force since the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act. Floor space per person; lowest in the OECD, below Japan. Average age of a first home buyer: 38 years. Social housing: extremely costly to taxpayers and stressed by a shortage currently in the millions. Social mobility, low; prospects of property ownership, low; social alienation, high.

See also my comment, "The Big Picture", below.

Liberalization and Density are not Mutually Exclusive

I agree with most of your argument. I like dense, walkable communities. I'd like to see the city gradually allow development in the ATR, while zoning it for high density.

Brit who moved from London to Vancouver just after the olympics

* love the trees, breathable air, empty streets

* love swimming in the sea after work on a Wednesday evening

* love the mountains

* love stanley park, and the decision to keep outside downtown low-rise

* hate the height of cars parked all along every street and four-lanes of cars whizzing through town everywhere

* hate that they're happy with an every-15 minute "frequent" bus service

* hate all the applauding a single two-way (confusing!) segregated bike lane

* hate the general self-congratulatory "best in north america" chatter: talk about a low bar

* pay proportionally the same in rent vs salary (didn't notice this as a hit moving here, compared to noticeably cheaper electricity bills and higher phonebills)

* find amusing all this talk of "foreign buyers" and "limited land" keeping prices high - reminds me of the UK in 2005, and probably Japan before its lost decade, Vancouver is clearly in a bubble (9x!?) sustained by belief that house prices always go up and that Chinese rich people don't know how to do math (in the UK it was always arab buyers who were presumed financially illiterate)

Apparently everyone was upset that they built the tube (Canada line) out to areas where no-one lives, rather than into the middle of pre-existing burbs. This is apparently so they can build new dense mixed-use areas around them. I like that thinking.

Wow -- a great success story!

Very good article. It definitely shows the strong desire people have to live in a "dense mixed use development," as the article shows. People are hungry for this kind of development, and people are willing to pay a great deal of money to live there.

New Geography is providing a service to developers and urban planners everywhere who should take note: dense, mixed use development is a hit! And, moreover, this type of success should not be out of reach of middle class and all people. We should encourage, allow, and nurture this living pattern everywhere. With more supply of this in-demand living arrangement, no doubt the price would come down, and people of all income levels can enjoy dense, mixed use developments. Policies should be in place to encourage it, and subsidies for sprawl and suburban developments should be ended.

I salute New Geography for its advocacy of dense, mixed use developments and their high degree of desirability!

Look to appropriate density, not sprawl or inclusionary housing

I have to submit my opinion that the best way to deal with escalating home prices in a naturally expensive market it not to embrace sprawl or to apply band-aids like inclusionary zoning, but to continue to allow more density in more places. If sprawl were the answer, L.A. would be affordable ... if urban growth boundaries by themselves were the culprit, Portland would not be the cheapest city on the West Coast ...

These types of articles always attack "land use regulation" and equate it with smart growth, while glossing over that the most common, and most damaging land use regulations are those that mandate large minimum lot sizes, single-family homes and large parking lots, limiting the ability of the market to respond to the need for housing and driving up the cost of infrastructure, which is largely borne by new development. (Minimum lot sizes were cited as the primary driver of housing cost in the book "A Better Way to Zone.")

Abandoning the growth boundary will not make housing in desirable Vancouver any cheaper, while housing in far suburbs across the Fraser River is already reasonably-priced. Sprawl may at first make housing cheaper on the periphery, but eventually you end up with terrible traffic congestions and as you push the limits of how far people can commute, home prices go up anyway.

I believe the region can encourage enough multi-family housing to be built in sufficient quantity to meet rental and condo demand. For households desiring a single-family type of living situation, allowing compact or row housing in sufficient quantity to meet market demand, in locations within walking distance of transit, is the best solution to provide affordable alternatives. This is after all a major metropolitan area.

Once you hit several million population, the idea of everyone living on the quarter acre and driving everywhere becomes untenable and unaffordable, but too often we use zoning regulation to push this living style, driving up costs.

In all seriousness Vancouver

In all seriousness Vancouver sounds like a carbon copy of the San Francisco Bay Area. I should know because I live in the Bay Area. I've been here for 11 years and moved from North Carolina. Thus my perspective is one of cynicism seeing as how a pretty nice house in a nice neighborhood in North Carolina- which doesn't have half-bad weather and somewhat mild winters- will cost you $200,000 or less. In fact, one of my friends back there bought an older house for $89,000 recently.

The same home in the Bay Area would be around $550,000, if not more if its in a "good" neighborhood with (gasp) actual functioning public schools. The general attitude of the small Bay Area town I live in is that any and all new housing is a BAD thing and that lord help us all if anything new is built because as we all know, more housing would just totally ruin the quality of life for everyone. If any actual plans come to fruition which these days includes such fantastic layouts of communities with "walkable" neighborhoods, rail lines, bicycle lanes, and mixed-use housing, again- the local community balks and nothing is ever built. Instead what we have is a beautiful neighborhood filled with quaint old houses that all have enormous price tags that nobody can afford. Well- I guess some can afford because people somehow still buy them, which is a mystery to me because my wife and I make a healthy 6-figure income and for us, buying here would be astronomical.

In North Carolina the state almost bends over backwards to get land developers and companies to relocate or build there. They're building houses in every former tobacco field and on every former farm. HUGE gigantic houses slapped up as quickly as possible. This is surrounded by a fleet of fast food and chain eateries, big-box stores, and so on. On the other hand the surrounding towns and cities are filling up with your typical brand of gentrified entertainment in the form of art galleries, microbreweries, wine bars, and the occasional Japanese restaurant.

As you can tell I'm somewhat bitter about the whole thing. It is aggravating to me that at one time, ordinary people with regular jobs could afford to live just about anywhere they wanted in the US. Its hard to imagine that San Francisco was once a longshoreman's town. Now its basically a playland for the old folks who got here first and the rich who drive their bimmers up and down 101.

Ok, so basically it sounds

Ok, so basically it sounds like the main reason Vancouver is so expensive is because its the only Canadian city that doesn't have absolutely crappy weather in the winter. It appears that in general the weather is about as good as you might find in roughly 70% of the US, yet since its in Canada and if you're a Canadian you have few choices for living in a city with halfway decent weather, Vancouver is it. Sounds totally like the California of Canada.

Like I said, it's a

Like I said, it's a naturally expensive market. Having said that, preventing development has made the situation worse. There's basically a fixed supply of land, and increasing demand.

A false choice between compact living and affordability

You make a pretty strong case for how urban growth boundaries raise housing costs. But before we can conclude that this effect alone should discourage us from adopting Smart Growth measures, its worth considering the costs of low-density suburbs. So suppose Vancouver were to adopt the policies its American counterparts did in the mid-20th century, and fully support fringe development? Well, for one, new highways would have to be built. In addition to the direct construction costs of such an endeavor, extremely valuable urban land would have to be acquired and cleared. The noisy and intrusive infrastructure would harm land values (although I suppose making a place undesirable is one way to make it affordable). The new suburbanites would require new infrastructure and rely more on their cars to drive longer distances, raising transportation costs. More sedentary lifestyles resulting from more time behind the wheel leads to higher public health costs. As automobile infrastructure comes to dominate the landscape, traffic congestion spurs a wave of NIMBYism that leads to low-density zoning, which can inflate housing costs just as much as UGBs. These costs may be harder to quantify but that doesn't mean they can be safely ignored, either.

I think what you're really saying about Vancouver is that its suffering from its own success. Natural geography, economic factors, and smart planning has made it an attractive and vibrant city. You can hardly fault its political leaders for creating a place where people want to be. You would have them accept the false choice of exlcuding the middle class or allowing sprawl. But why should compact living and a middle-class income be mutually exclusive? After all, all else being equal, living on less land is more affordable.

Instead of adopting the American suburban model, which would damage the very qualities that make it attractive, Vancouver should find more innovative ways to address its affordability problem. Maybe it can expand its secondary suite zones. It could also selectively extend its grid into the least agriculturally productive or environmentally sensitive land. By investing in transit infrastructure, the city can accommodate higher residential densities.

Point is, there are plenty of ways to expand the housing supply without incurring the costs of American-style suburban development.