My Defining Rust Belt Urbanism piece three weeks ago, in which I discuss the themes of what would drive Midwest urban rebirth, prompted a great question. Bloomberg Opinion columnist, CSY subscriber and avowed Sun Belt enthusiast asked me on X (formerly Twitter) – what does Rust Belt success look like?

It’s a good question, because there are lots of people who don’t think there is much of a path to success for the urban centers of the nation’s heartland. Most of today’s urbanists seem to believe the templates have been set already. One is to get with the program forged by the coastal cities, leaning into a winning economic sector you’re uniquely suited for, or continue to fall behind. Another other option is to get with the program touted by Sun Belt cities. Market lifestyle, climate and affordability, and watch the people roll in.

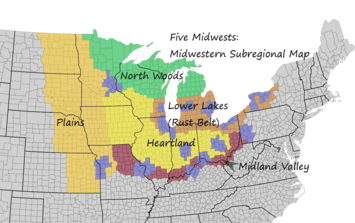

In reality, urban rebound is much more complex than either of those examples would imply. Yet the fact remains that the path to success has to be tailored to the place. Before going into the ways that Rust Belt cities can turn around, let’s dig a little deeper into how coastal and Sun Belt metros reversed their fortunes and made economic leaps. (A parenthetic comment: I’m using the term “Rust Belt” here, but really writing about the largest metros within the twelve-state region most people generally call the Midwest – Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska and Kansas. I often use the terms interchangeably.)

The Coastal Cities Template

There’s one key difference between coastal cities and Rust Belt cities that is rarely recognized. Through the middle of the 20th century, coastal cities indeed had strong manufacturing economies cities like those in the Rust Belt. Yet they also grew and developed with stronger corporate and service economies. Using the three-sector model of economic activity, from their beginning coastal cities were able to develop a blend of primary (resource extraction), secondary (manufacturing) and tertiary (sales, transport and distribution) economic sectors. That allowed coastal cities to build on their assets from tertiary economic output (universities, hospitals, financial services, media and publishing) that formed the foundation of the knowledge or creative class economy that drives them today. With a weaker tertiary sector that didn’t produce quite the same output as that of the coastal cities (and probably an implicit acknowledgement made by people throughout the country that the coastal outputs were better than those in the middle of the country), Rust Belt cities lagged.

Coastal cities were then ready for a period in which the global economy leaned in their favor. That economic shift allowed them to stabilize local economies more quickly. It allowed them to focus more on quality-of-life improvements that led to reduced crime, improved schools and other public services. Coastal cities were ready to appeal to a demographic that was increasingly demanding what they offered.

Read the rest of this piece at The Corner Side Yard.

Pete Saunders is a writer and researcher whose work focuses on urbanism and public policy. Pete has been the editor/publisher of the Corner Side Yard, an urbanist blog, since 2012. Pete is also an urban affairs contributor to Forbes Magazine's online platform. Pete's writings have been published widely in traditional and internet media outlets, including the feature article in the December 2018 issue of Planning Magazine. Pete has more than twenty years' experience in planning, economic development, and community development, with stops in the public, private and non-profit sectors. He lives in Chicago.

Chart:courtesy The Corner Side Yard.