The combination of renewed interest in Tonya Harding (due to the film, I, Tonya) and the winter Olympics made me think of class and sport lately – especially sports that involve snow and ice. Although winter sports might be considered quite ordinary for some who live in very cold climates (such as Norwegians), most require expensive equipment and travel.

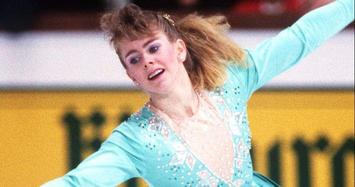

Harding’s story illustrates this quite well. She came from a working-class family and trained in an ice-rink located in a shopping mall. Based on the representation of her life in I, Tonya and in documentaries about the skater, she struggled to fit in with her peers because she lacked the cultural and economic capital. Her costumes were home-made, her hair was too big, and her muscular frame lacked the expected look of a figure skater. This doesn’t excuse any involvement she may have had in the attack on Nancy Kerrigan (herself from a working-class background), but Harding’s ‘rough’ ways made her an outsider from the beginning of her career. In many ways she was an imposter in the sport.

Working-class people remain outsiders in winter sports, as the current Olympics show. Watching the amazing feats of the athletes is quite thrilling. The jumping, sliding, and skating at break neck speeds is impressive. But to get to this level, athletes need significant resources. Unlike Harding, most winter athletes have had enough financial support from their families to enjoy regular visits to ski areas, skating lessons, and expensive equipment. Even if a working-class person lived in a cold climate, near ski resorts, what are their chances of spending time there – outside of working at the resort?

I don’t mean to disparage the athletes I’ve been watching on television. Many have had struggles to overcome, and their stories are presented as inspiring. We hear about the years of sacrifice, the grueling training schedules, and overcoming injury. Hard work and determination are celebrated. While these seem like working-class values, a deeper look makes clear that these are stories of privilege. No doubt, Olympic athletes have worked hard, but their success doesn’t demonstrate that ‘anyone can do it, as long as you dream big’. We hear about families moving closer to facilities or forgoing vacations and leisure activities in order to train. Parents have left their jobs to focus on supporting their athlete children. But these sacrifices require money and networks. A parent earning minimum wage on a casual contract can’t leave their job to spend all day at the ice-rink. Most can’t even afford the lessons. And even if a potential Olympian is scouted and sponsored, most working-class families don’t have the means to move closer to a training facility. Plenty of working-class families work hard and have ambitions, but they need capital to realize those dreams.

Why does the lack of class diversity in Alpine sports matter? Will it improve the lives of working-class people to see athletes from working-class backgrounds? Should working-class people just ignore the winter Olympics and stick to watching soccer, football, track and field and rugby league — sports that we might have a chance of participating in? The answer lies in the value of sports in general. Athletic endeavor inspires us. We love stories of athletes overcoming obstacles to compete, especially when a competitor comes from a background like our own. Sports people can be important role models for working-class youth, especially if they use their influence to speak truth to power. Think Muhammad Ali, Billie-Jean King, Serena Williams, or Adam Goodes (Indigenous Australian Rules Football player). For a working-class young person, watching someone like them compete in a sport that is outside of their current possibilities demonstrates that working class people belong in all areas of life. And lack of diversity matters overall, a point that is ironically reflected in the praise for the diversity of this year’s US Olympic team. The 244-person team includes ten Black and eleven Asian-American competitors.

Sport is also important for working-class communities. Support for a team brings people together, helping to create and maintain a sense of collective identity. It provides a release from the grind of everyday life and can even provide a livelihood for some working-class people.

The amazing tricks performed by the aerial skiers or the snowboarders don’t represent possibilities for most working-class people. Of course, a few working-class athletes – like Harding – have made it to the Olympics despite the classed odds being stacked against them. But exceptions don’t counter the rule. For the most part, the glamour of the ice-rink, the sparkle of the piste is out of reach for working-class sport fans and remains another of the domains reserved for the middle and upper-classes. It doesn’t really matter whether the working-class kid in inner-city London, the western suburbs of Sydney, or rural America actually wants to take up the luge. The point is that working-class people should be represented across all aspects of society.

This piece originally appeared on Working-Class Perspectives.

Sarah Attfield is an associate lecturer in communication in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Technology Syndey. Her scholarly work is focused on social class in popular culture and literature, particularly the representation of working class life. She has published work on UK grime, dubstep and hardcore punk as well as on working class poetry. Her poetry has been published widely in Australian literary journals, and she has performed her poetry in a variety of venues across Australia.

Photo: Via iheartRadio.com.