Traffic crashes are a cause of ill health, impaired living or curtailed lifespan. Does city growth, in its sprawl-type outward expansion, increase the incidence of fatal and injurious crashes? This factor is the latest addition to numerous attempts to pin a correlation or causality linking traffic accidents with any number of causes.

The twentieth century is not the only time in city evolution at which traffic accidents became a concern. Around the end of nineteenth century, when all in-city transportation was hoof and foot-dependent, accidents in cities were common.

In New York, for example, 200 persons died in accidents in the year 1900, which, when transposed, means a 75 percent higher per capita rate than today. In Chicago the rate per horse-drawn vehicle in 1916 would be almost seven times the per auto rate in 1997.

These are surprising, counter-intuitive statistics: the two cities, as all others at the time, were not just walkable, they were predominantly foot-based cities; exemplars of urbanism. No person had to cross six-lane arterials or dodge high-speed vehicles. Distances were short, city blocks small, densities high, and personal daily routine took place mostly on foot. It seems paradoxical that a walkable, dense, mixed-use city would generate high fatality rates; and more so because the speed of traffic ranged between 3 and 9 m/hr : half or less the 20 m/hr threshold beyond which fatalities increase. Without sidetracking for explanations, we can draw at least one simple idea from this past: a dense, foot-based city can generate high rates of fatalities.

Soon after motorized transport entered city streets, fatal crashes rose. In the face of appalling and rising death figures, many adjustments occurred over a 30-year period. None of these changes involved urban form; they were inevitably operational and regulatory (e.g. lane markers, stop signs, driving rules, etc).

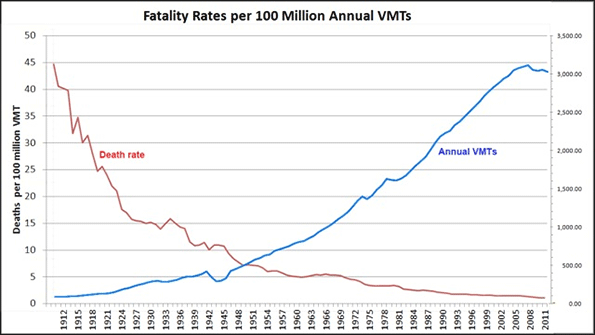

In the U.S. during the first decades of the automobile’s presence on city streets, car accident rates fell rapidly even though car travel tripled between 1920 and 1955.

During the same period the urban form characteristics remained fairly stable. The modest suburban expansion of cities at that time was light-rail dependent; “motopia” had yet to emerge . Most urban form of the '30s and '40s was generally similar to the early twentieth century prototypes: medium to high density compact development around a rail line or station with a core of amenities and services. It is nearly impossible to determine whether or not this form played a role in the drop in fatalities, due to the absence of concurrent alternative forms. When new “motopia” forms emerged, trends in fatalities did not bear out their influence.

When automobile dominance was firmly established and new highways opened vast tracts of land for city growth, urban form at the city periphery changed decisively from compact, mixed use, walkable and transit-centered to typical “motopia” or “sprawl.”

Despite a Smart Growth America recent claim of a correlation between sprawl and an increase in fatal accidents and a small decrease in injuries, the traffic fatality rate actually decreased as U.S. cities sprawled and total VMTs increased.

The current level of traffic fatalities stands at about one third of the 1955 level and less than 1/20 of the 1925 rate. Intriguingly, sprawl at the national scale did not produce an increase in fatal or total crashes as analysts predicted. If the sprawl paradigm did play its negative role, then other countervailing factors must have had a greater influence that overshadowed its effect.

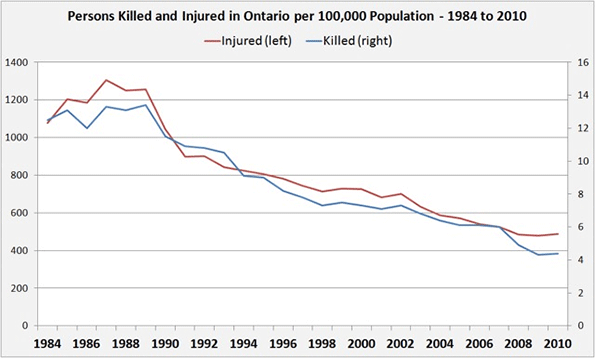

The national trends in Canada mirror those of the U.S. Notably, fatal crashes fell at a faster rate than injuries, increasing the uncertainty about the correlation that links a substantial rise in fatalities with a rise in “sprawl-ness”. Provincial statistics show similar trends. The chart below shows the trends in Ontario, the most populous Canadian province:

During a quarter century of more suburban expansion, fatalities and injuries followed a similar decline for a respective drop of around 70 percent in fatalities and about 60 percent in injuries; a substantial change. Like the national level statistics, provincial ones reinforce the uncertainty about a correlation between urban form and traffic fatality rates; instead of upward climb, we see an unmistakable decline.

But what do statistics show at the finer, city scale?

We turn to two – Toronto and Calgary – of six Canadian cities whose sprawl has been documented in detail. In spite of their anti-sprawl policies, in most the movement was retrograde, toward more sprawl.

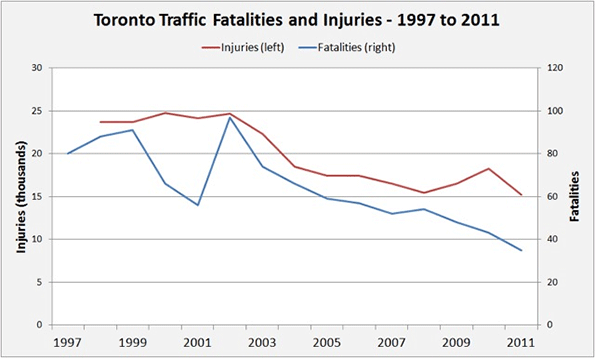

The graph above shows Toronto's trend in fatal crashes and injuries for the period of 1997 to 2011. Toronto during these 15 years can be characterized as a suburbanized region (with a few exurban appendices) that continues to expand using the conventional development model.

In addition, Calgary, Alberta, the “car capital of Canada”, according to a Smart Growth report, has Canada's lowest overall density; it remains a sprawled city. As with the national and provincial trends, the two cities’ traffic safety trends show a persistent overall drop in fatal and injurious accidents. Once more, the city-level fatalities and injuries trends contradict the correlation that links sprawl-type urban form with an increase in fatal accidents and a decrease in injuries. Whatever the countervailing factors are, they mask and overwhelm an expected rise in fatalities. As for the decrease in injuries, the actual drop is far greater than what the postulated correlation would predict and cannot be explained by it alone.

If at the national, provincial and city levels the trends are positive in spite of the negative direction of urban form, the health concerns that would justify planning interventions appear to have been alleviated on this front, at least for the first century of automobility and for the half century of uninterrupted sprawl.

One might speculate that had growth been in a compact, walkable, diverse use, transit-centered form, fatalities could have declined even faster. This could well be true but cannot be deduced from the above statistics. Regardless, the current trends could not be seen as a cause for concern and urgent action on the urban form front. On strictly health grounds, cities and provinces are progressing in the right direction. There is no apparent imminent or growing threat.

So far we have seen the difficulty of explaining the persistent drop in traffic fatalities via a correlation with “sprawl-ness” and we hypothesized that other factors may be at work. Indeed they are. We find several in overlapping lists of international, national, provincial and city documents: some linked to the causes of fatal crashes, others as government directives. Here is a collection in no particular order of importance:

Speed limit range/control

Drinking and driving laws

Young driver restrictions

Intersection geometry

Car crash-worthiness rating

Car fitness regulations

Road condition care

Driving fitness/age

Speeding penalties

Vulnerable user protection

Motorcycle helmets

Seat belt use/air-bags

Child restraints usage

Pre-hospital, on-spot care

Distraction prohibitions

As one example of the potential effect of safety measures, NHTSA in 2005 estimated that 5,839 lives would have been saved in 2004 (or 14 percent of total car-related fatalities) if all passengers wore seat belts.

Planning interventions can have multiple beneficial effects. On at least one front there is no cause for alarm or a rationale for a call to arms; the battle against traffic fatalities is being won, without urban form change. This does not suggest that a correlation between sprawl and the reduction in fatal and injurious crashes exists, or imply that sprawl is a desirable urban form. It simply means that the effect of urban form on crashes cannot be established unequivocally and therefore cannot be a lead driver for action.

Fanis Grammenos heads Urban Pattern Associates (UPA), a planning consultancy. UPA researches and promotes sustainable planning practices including the implementation of the Fused Grid, a new urban network model. He is a regular columnist for the Canadian Home Builder magazine, and author of Remaking the City Street Grid: A model for urban and suburban development. Reach him at fanis.grammenos@gmail.com.

After twenty-four years at Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Tom Kerwin now leads an active volunteer life, including being the Science and Environment Coordinator for the Calgary Association of Lifelong Learners. He holds a Master’s degree in Environmental Studies from York University.

A different version of this article appeared at SustainableCitiesCollective.

Flickr photo by 7mary3: a car accident due to an unsafe lane change.