Bookstores and libraries have long played a central role in fostering a deeper appreciation of knowledge, and in lifelong learning. Increasingly, these places are also filling another critical need in our communities, by providing a haven for those seeking a communal connection in an ever-more isolated world.

Ray Oldenburg, author of The Great Good Place, coined the term “third place” to describe any environment outside of the home and the workplace (first and second places, respectively) where people gather for deeper interpersonal connection. Third places include, for example, places of worship, community centers, and even diners or pubs frequented by the “locals.”

Third places, according to Oldenburg, are vitally important to the social fabric of communities because they facilitate the healthy exchange of ideas and provide a public venue for civil debate and community engagement.

Libraries and bookstores clearly are long-time ‘third places’ That shouldn’t be a surprise, given that books serve as the lingua franca of new ideas. Notice, though, that these establishments frequently provide coffee bars, meeting rooms, Wi-Fi access, public computer terminals, and other amenities. They serve as accessible retreats for community groups and clubs, offices for transitioning job-seekers or home-based business owners, logical meeting places for children’s literacy organizations, havens for latchkey kids, and bases of operation for homeless men and women as they try to reintegrate into the community. These are the features, probably more so than the rows of books and racks of periodicals, which grant libraries and bookstores their ‘third places’ status.

Libraries have been hit hard by the proliferation of home-based Internet access and digitized material. The impact is exacerbated by state and local budget cuts that place some libraries in a vicious downward spiral — reduced foot traffic from those with other options often is held out as “evidence” of library irrelevance, leading to more budget and staff cuts and further reduced access for those who need it.

Large libraries in major urban centers are particularly vulnerable, with their cavernous buildings and row upon row of books that are rarely touched. If libraries are to survive, city leaders and library boards must continue to explore creative solutions for the changing needs of their patrons. As economists would put it, they must “drive demand” for expanded library services.

A great example of success with this approach is the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library (www.sjlibrary.org) in San Jose, California. It purports to be the only institution of its kind: It serves as the primary library for both a major university and a major city. This joint partnership between the city of San Jose and San Jose State University was announced in 1997, and the primary building opened in 2003. It boasts over 7 floors and 1.6 million books. There are also dedicated rooms for quiet study sessions, teen activities and multimedia access. In effect, SJSU students have access to all the popular features of a typical public library, while the public has access to all the academic resources of a university library. The entire community is well served by this far-sighted collaboration.

It represents the convergence that is taking place between the traditional role that libraries have long played and the virtual world. According to a study funded by the American Library Association in conjunction with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the number of U.S. libraries nationwide offering public Internet access has ballooned from under 13% in 1994 to nearly 100% today. What this suggests is that the role of libraries as technology hubs is increasingly supplanting their function as simply a repository of books.

The use of community space in libraries to access technology is particularly vital for low-income residents and for individuals in small towns where the library may be the only connection point for free Wi-Fi access.

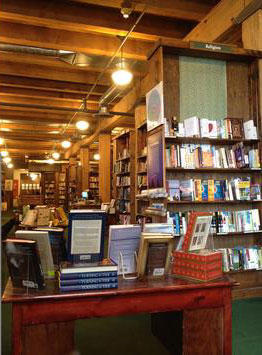

Bookstores are confronting the dual challenge of staying both vital and profitable. The most successful brick and mortar bookstores have evolved into third places. Once just exclusively retail outlets, they now are quasi-library/community gathering spots with onsite coffee shops and free Wi-Fi access. While bookstores have always attracted those who wish to browse and kill time, they now also draw others, laden with backpacks, to research, write, and study. Bookstore-based reading groups abound.

But even when a bookstore embraces its role as a third place institution, its viability is not guaranteed. The bankruptcy and closure of more than 600 outlets of Borders Books nationwide is evidence of a shakeout in the retail book industry, amid the proliferation of electronic book portals such as Amazon, Apple and Google. Independent bookstores especially have struggled to maintain their niche in the marketplace (although they may have more flexibility to quickly embrace third place-related amenities).

The lesson in this case is that capitalism can be harsh. For example, Amazon’s controversial price comparison tool allows shoppers to scan bar codes to check prices at rival brick and mortar and online stores. But capitalism also encourages differentiation. As every good business owner knows, becoming a commodity dealer and competing only on price usually is a recipe for failure.

Rather, libraries should be more like bookstores, creating an inviting, leisurely environment. Bookstores should be more like libraries, providing community rooms and programs.

Both should think creatively about how to provide the things that online sellers cannot. That includes, of course, the pleasures of shelf browsing as opposed to web-based browsing. But beyond that, the most successful libraries and bookstores will embrace the opportunities for relevance that their special third place status enables.

Michael Scott is a speaker and co-host of the Internet radio show Bookmark Radio. He can be reached at michael@bookmarkradio.com. Photo by the author of the Tattered Cover bookstore in Denver, Colorado.