As the country’s largest and densest metropolis, New York City has been able to offer a level of public transit service that most other cities can only dream about. Commuting to Downtown or Midtown Manhattan has been—and still is to a large degree—a remarkably easy affair for hundreds of thousands of residents, whose travel options include commuter train, subway, ferry and bus. However, like a lot of older American cities, New York has changed dramatically since most of those services were put into place, and more and more residents, particularly among lower-income workers, no longer travel to Manhattan for work.

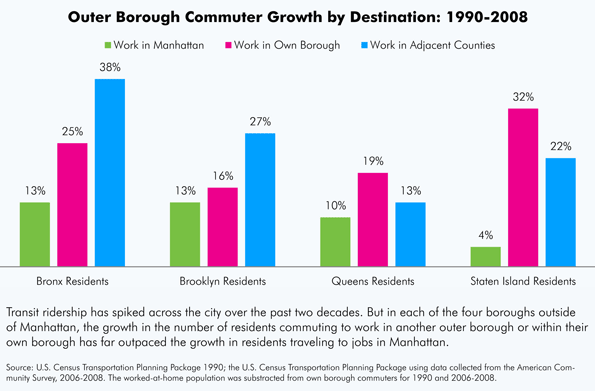

Census data show that between 1990 and 2008 the number of residents who traveled to work in their own borough or a neighboring borough or county increased much faster than the number who made the more traditional commute to Manhattan. For instance, the number of Bronx residents who traveled to Queens or Westchester County for work increased by 38 percent, and the number who traveled inside the borough jumped by 25 percent, while the number commuting to Manhattan increased by only 13 percent in the same period.

The discrepancies on Staten Island are even starker: During the same period, the number of Staten Island residents traveling to work inside their own borough increased by 32 percent, and those going to Brooklyn or New Jersey increased by 22 percent, while the number heading into Manhattan barely changed at all—a four percent increase in those 18 years. Although not as dramatic, Brooklyn and Queens both saw significant gains in non-traditional commutes as well. In fact, the number of Brooklyn residents traveling to Queens grew by 32 percent, compared to a 13 percent increase in the number going to Manhattan. In 2008 despite being a notoriously difficult trip for public transit riders, nearly 160,000 people crossed the Brooklyn/Queens border for work everyday.

One big reason for this shift in commuter patterns is New York’s changing economic landscape. For decades Manhattan has been steadily losing its share of jobs to the other four boroughs, but over the last ten years that process has sped up considerably. From 2000 to 2009, New York City lost a net 41,833 jobs, but that was because of the huge concentration of losses in Manhattan during 2008 (over 100,000 in that single year). Every other borough saw a net increase in jobs during that period. Queens saw 2.4 percent growth, Staten Island 4.6 percent growth and the Bronx and Brooklyn 7.7 and 7.9 percent growth, respectively.

It won’t come as surprise to those who have been paying close attention to the economy that robust job gains in the health care and education sectors are what lie behind sustained growth in the outer boroughs. Between 2000 and 2009, New York City gained nearly 120,000 jobs in those two sectors alone. And although Midtown Manhattan has several prominent hospitals and universities, collectively, the hundreds of hospitals, nursing homes, community health clinics, colleges and professional schools in the other four boroughs—from Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx and SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn to Queensborough Community College in Bayside—accounted for the lion’s share of jobs in those sectors.

New York City’s transit system wasn’t designed for commuter trips to jobs within and between boroughs outside of Manhattan, and as a result the city’s median commute times have been rising steadily for decades. According to American Community Survey data released last December, New York’s four outer boroughs all have median commute times that are north of 40 minutes, which puts them among the longest in the country. And among public transit riders they are significantly longer, ranging from 52 minutes each way in Brooklyn to a barely comprehensible 69 minutes each way in Staten Island.

In our study, we interviewed a number of outer borough employers who felt that a lack of dependable rapid transit service has exacted a toll on their businesses. A lack of transit effectively shrinks their labor pool, they said, and causes more turnover as disgruntled employees decide to leave rather than suffer through two hour commutes every day. The chief operating officer at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in East Flatbush Brooklyn even said that it could cause the hospital to rethink its plans for expansion. “I’ve been here 24 years,” he said, “and I still haven’t seen any improvements in mass transit.”

New York’s biggest investments in transit are still almost entirely focused on Manhattan commuters. Tens of billions of dollars are being invested in what amounts to an extension of the Q train along Second Avenue, a new Long Island Railroad tunnel to Grand Central, a one stop extension of the number 7 train on the west side, and a Santiago Calatrava-designed Fulton Street Station in lower Manhattan. A new Moynihan Station on 34th Street is apparently next on the agenda. These projects may spawn billions more in lucrative real estate deals, but they don’t reflect the city’s true economic geography.

A lack of transit investments in the outer boroughs might be understandable if these new outer borough jobs were spread out evenly over a large territory, but a huge percentage are located in relatively dense clusters. Over 20,000 commuters descend on the SUNY Downstate and Kings County Medical Campuses — right across the street from each other —every morning, for example. But very little has been done to facilitate commutes to that area, and many employees and patients depend on a dizzying array of livery cabs and dollar vans to get them where they’re going. Similarly, JFK airport in Queens is home to over 55,000 jobs; Hunts Point in the Bronx 20,000; the Sunset Park waterfront in Brooklyn 32,000, and so on.

Making much needed investments in service and upgrades to the bus system may not be as sexy as a new train terminal in Midtown. But if New York is going to sustain job growth and retain a truly world-class transit system, then it will have to start looking beyond Manhattan and invest in solutions that make commutes to job centers in the outer boroughs easier for residents.

David Giles is a research associate at the Center for an Urban Future, a Manhattan-based think tank. He is the author of Behind the Curb, a Center for an Urban Future report about the gaps in transit service in the four boroughs of New York City outside of Manhattan, from which this article was adapted. For the whole report, please visit BehindtheCurb or www.nycfuture.org.

Photo: The Brooklyn Bridge by S J Pinkey