I’ve written some versions of this topic many times over the years. Now it’s time for the latest installment.

Every so often, there are people who want to cast “cities” (here I’m defining them as the core or foundational municipality of a larger metropolitan region) against “suburbs” (the non-core, usually smaller jurisdictions, that have an economic, social and cultural connection to a core city). Every so often, people want to use various metrics to demonstrate that either cities or the collective suburban areas are doing better or worse than the other.

Researchers of all types on either side of the city/suburb divide will cherry-pick data to prove a point about cities or suburbs. I could bore you with a long historical explanation of this divide, but the tl;dr version is that as cities were beset with economic and social issues in the mid-20th century, and as “suburbs” had grown to a point where they had their own constituency and political representation at the same time, the line between the two was drawn. In the early 21st century, many cities recovered and saw revitalization. However, those committed to suburbs were quick to suggest that not all is well with cities.

The Covid pandemic period had plenty of examples of this pushed forward by suburban advocates. Two examples stand out. When researchers saw a surge in city out-migration in 2021 and 2022, many were saying the pandemic was causing people to flee cities in favor of more spacious and pleasant suburbs, exurbs and rural areas. Suburbs offered more comfort and protection than the more-crowded cities. When downtown office buildings effectively shuttered because of the pandemic shutdown, and office workers finally took advantage of meaningful ways to work from home, many people were saying that office-centered downtowns that were reliant on office worker traffic were doomed; if a worker could work principally at home, one could live anywhere, potentially threatening the very existence of cities.

Of course, there were city advocates (I include myself) who pushed back on those narratives. For one, I maintained that cities had an “experiential advantage” over suburbs that would survive the pandemic. There are amenities and attractions that cities have that still bring people to cities, and there are people who will still choose to live in an amenity-rich environment.

On the other hand, there are city advocates who are priced out of expensive cities, and getting behind the YIMBY and/or abundance movements to increase the supply of housing in cities and suburbs. Many YIMBY activists have become deeply involved in zoning reform in large cities, promoting the elimination of exclusive single-family zoning districts and increased housing density in transit-accessible areas. To address the same issues in suburbia, many YIMBYs have taken to proposing statewide legislation at state legislatures, encouraging states to take a more direct role in shaping local land use and zoning policy.

Read the rest of this piece at The Corner Side Yard.

Pete Saunders is a writer and researcher whose work focuses on urbanism and public policy. Pete has been the editor/publisher of the Corner Side Yard, an urbanist blog, since 2012. Pete is also an urban affairs contributor to Forbes Magazine's online platform. Pete's writings have been published widely in traditional and internet media outlets, including the feature article in the December 2018 issue of Planning Magazine. Pete has more than twenty years' experience in planning, economic development, and community development, with stops in the public, private and non-profit sectors. He lives in Chicago.

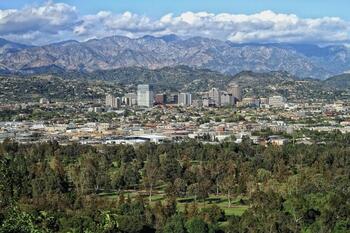

Photo: Renee Silverman via Flickr under CC 2.0 License.