I’ve been a big fan of Alan Mallach of the Center for Community Progress for years. I first met him at a Cleveland Fed conference in Cincinnati in 2017, and later interviewed him at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy regarding his book The Divided City: Poverty and Prosperity in Urban America. I’m grateful to have him as a regular reader of this newsletter. And, since he said I could use this quote as a blurb, let me add that via email he said the Corner Side Yard is “consistently interesting and often thought-provoking.” Thanks!

Anyway, he reached out to me last week after I’d written about the lack of research on Rust Belt-to-Sun Belt migration in America, and its impact. He noted, quite correctly in my opinion, that there’s also been little research on white flight as well – the migration of whites from cities to suburbs throughout the latter half of the 20th century, while a major influx of Blacks into Northern cities was also taking place. In his email, he said that “from a social/cultural perspective, it's clearly problematic, and thus not an acceptable topic for research. The fact remains that, in round numbers, while the Great Migration led to 5 million Black people moving to northern cities, simultaneously 15 million white people left those cities.” (Note: this is something I first saw documented in an academic paper by Leah Platt Boustan published in 2007).

“White flight” all along

Mallach wrote and published his own academic paper last year on a similar topic. Mallach’s paper entitled Shifting the Redlining Paradigm: The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Maps and the Construction of Urban Racial Inequality resulted in some fascinating findings. From his paper abstract:

“While it is important to recognize the racist roots of contemporary urban conditions and Black disadvantage, the focus on the HOLC redlining maps of the late 1930s, which have become a staple of both research and popular literature, is misplaced. Despite statistical associations between the maps and contemporary measures of racialized disadvantage, extensive research has found no evidence to support a connection between them. Instead, the Second Great Migration and white flight, both acting in the context of the exclusion of Black buyers from the growing suburbs, led to the spatial and economic bifurcation of urban Black populations within cities and the reconfiguration of the formerly predominately white ethnic redlined areas as segregated areas of concentrated Black poverty.”

In other words, redlining didn’t segregate American cities. White flight, fed by the Second Great Migration that brought millions of Black people to Northern cities between 1940-1970, did. White flight perhaps wasn’t always racist in its intent, but it was definitely racist in its practice.

That’s too bad, because redlining, and a whole host of other policies, did a lot of heavy lifting in the 2010s to describe racial inequality. Turns out America didn’t need a racist federal policy to resegregate Northern cities; it just needed an economy in need of workers, and a housing development industry finally willing accommodate the needs of a housing-starved public. Sound familiar?

Mallach says that the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation’s “residential security” maps, developed between 1935 and 1940, assessed sections of cities on a scale of A to D, with associated color codes: A (green, meaning excellent residential security), B (blue, for good residential security), C (yellow, for fair residential security) and D (red, indicating poor residential security). Neighborhoods with higher grades were deemed safer for bank investments; lower grades were considered “hazardous”.

Read the rest of this piece at The Corner Side Yard.

Pete Saunders is a writer and researcher whose work focuses on urbanism and public policy. Pete has been the editor/publisher of the Corner Side Yard, an urbanist blog, since 2012. Pete is also an urban affairs contributor to Forbes Magazine's online platform. Pete's writings have been published widely in traditional and internet media outlets, including the feature article in the December 2018 issue of Planning Magazine. Pete has more than twenty years' experience in planning, economic development, and community development, with stops in the public, private and non-profit sectors. He lives in Chicago.

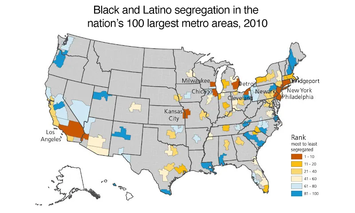

Photo: A map showing Black and Latino segregation in the nation’s 100 largest metro areas in 2010. Source: https://metroplanning.org/the-cost-of-segregation-2/