I have always been skeptical of the use of labor statistics. In 2009, I began to write in Working-Class Perspectives about the de facto unemployment rate, because official reports on the unemployment rate in Youngstown left out much of the story. Drawing on traditional Bureau of Labor Statistics data as well as comparative studies from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, I looked beyond how many people were looking for work to add figures for how many were underemployed, discouraged, or unable to work because of disability. I also factored in those in government support programs or in prison. Using these figures, I showed that Youngstown’s unemployment rate was not 7.2%, as officially reported, but over 25%. I followed up later with stories that considered the de facto unemployment rate nationally, especially during the Great Recession. My approach was picked up by others, including Christopher Martin, who wrote about it here earlier this year, and the Wall Street Journal.

Recent discussions of employment make me skeptical again. The New York Times reported that 4.3 million people quit their jobs in August, while 10 millions jobs went unfilled that month. Reports on the lower than expected return to work as the pandemic recedes have described it as a Great Resignation or the Great Reshuffle. Media stories have highlighted an increase in early retirements and “sick outs,” some, perhaps ironically, focused on resistance to vaccine mandates. The service, hospitality, leisure, government, and manufacturing sectors have been especially hard hit. Like the Wall Street Journal, many have been left wondering “Where Did All the Workers Go?”

Commentators explain these patterns in several ways: apprehension about returning to the workplace as the pandemic continues; difficulty in finding affordable childcare and eldercare; reconsidering the centrality of work and work/home life; increased government assistance; supply chain shortages. Many of the discussions argue that the change primarily reflects the personal choices of workers (agency), especially those in working-class occupations and industries.

While these stories sometimes quote managers whining about not being able to find enough workers, they often ignore how businesses have contributed to this shift. Some companies used the pandemic to implement or expedite planned workplace reductions. For example, the pandemic led some businesses to increase capital spending on technologies and automation that displaced employees and closed or moved worksites. Increased use of self-service kiosks and QR codes, Zoom meetings, and various forms of artificial intelligence have reduced the need for workers. Others found that the possibility of remote work allowed them to close offices or relocate outside of traditional work centers.

The pandemic and the use of just in time production has contributed to uneven inventories and supply chain disruptions. In some cases, supply chains disruptions have resulted in downsizing even as the intensity of work increased. With fewer workers, the remaining employees sometimes have no work and sometimes have too much. Of course, this is being touted as a gain for business efficiency and flexibility. While wages have increased for some, a recent study from the Economic Policy Institute shows that wage inequities have worsened. Most people these days are working harder and faster — and often with less job security. Given the new conditions, some workers are choosing to quit and seek employment elsewhere.

Read the rest of this piece at Working-Class Perspectives.

John Russo is an affiliate of the Kalmonovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University and the co-author of Steeltown U.S.A.: Work Memory in Youngstown.

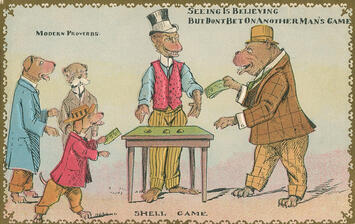

Photo credit: Vintage postcard, by Steve Shook via Flickr under CC 2.0 License.