I was in Atlanta last month and was encouraged to poke around by the people who invited me. For my entire life the greater Atlanta metroplex has grown in population, geographic size, economic importance, and cultural relevance. As the locals like to remind everyone, Hartsfield-Jackson is the busiest airport in North America. Half the people I went to school with in New Jersey in the 70s and 80s migrated to places like Atlanta for all the usual reasons.

On my flight I sat next to a chatty couple who lived in what they described as a brand new 3,800 square foot house they bought for under $300K a few years ago. It was on the outer edge of Gwinnett County well outside the Atlanta city limits. They bought it because it offered lots of space, a big yard, a good school district, low taxes, and a half hour commute to their respective jobs which were in opposite by equidistant directions. This is the dominant American drive-till-you-qualify model of middle class suburban housing.

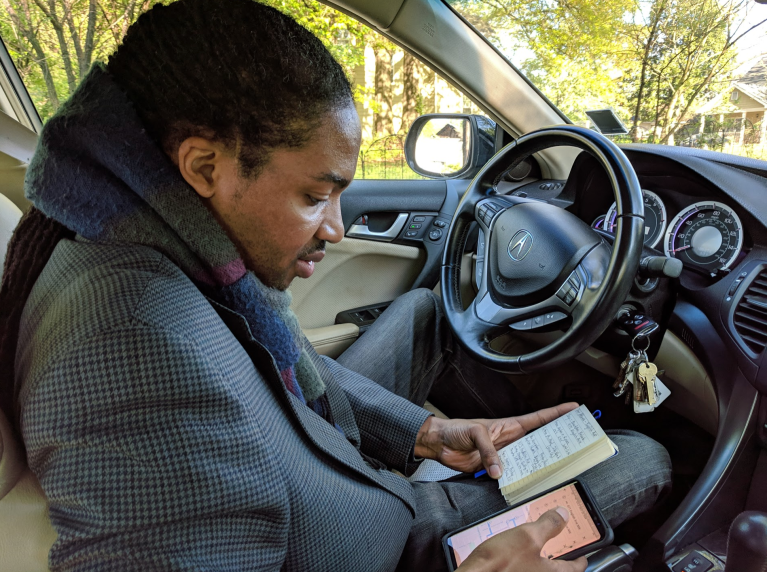

I chatted with a Lyft driver who explained his choice of neighborhood when he bought his home. He and his wife were focused almost exclusively on the quality of the schools their kids would attend. They paid significantly extra for a smaller less desirable home because of which suburban school district it was in. Commuting in to the city and Lyfting on the side was one of the ways he paid the bills.

As the middle class migrated out to shiny new developments on the periphery older suburban neighborhoods declined. The economic and cultural vacuum that formed lowered property values, suppressed rents, and encouraged an attitude of benign neglect from local government.

But a decade or so ago select older neighborhoods were identified by people who saw an advantage in these close-in areas. Property was super cheap and travel to downtown jobs and amenities was easy. Statistically only a quarter to a third of American households have school aged kids so these were mostly childless folks who were focused on other neighborhood characteristics. And these locations still offered fully detached homes with a garden because they were suburbs – just older and a lot closer in.

For people willing to take a risk and renovate properties in the right funky neighborhoods the upside can be significant. The process of decline goes in reverse and forms a virtuous cycle of new investment, increased value, higher rents, and boosted tax revenue. Money translates to political will and better government services once officials cotton on. And so long as you don’t change the existing buildings beyond basic maintenance and cosmetic upgrades the authorities generally don’t get in your way.

If good schools attract people with kids, then the appeal for other kinds of folks is often walkability. Driving twenty minutes to buy milk and eggs or get a cup of coffee isn’t as desirable for this slice of the population than walking to a corner shop. Can you twist your way through the cul-de-sacs of a newer development and find what you need at a strip mall on the side of an eight lane arterial road on foot? Sure. Do people enjoy doing it? Not so much. Reviving older Main Streets sometimes translates into bringing back the surrounding territory from economic decay.

There are two theories about how and why neighborhoods pivot from decline to reinvestment. One says market demand and a shifting culture lead the process of revitalization. Lending institutions gradually change their attitudes about risk and lending. Then slowly and reluctantly government begins to bend to the larger swing once tax revenues increase and voters and business interests exert themselves on the political process.

The other theory says government makes up front investments in public infrastructure and services which then embolden new private investments and help change the larger culture. I tend to believe it’s a little of both mixed with luck and good timing. I know of plenty of places where the private sector has attempted to invest in an area, but the political process stymied progress at every turn. I also know of examples where government invested in things the market and culture didn’t value so the new infrastructure sat vacant for thirty years with no takers.

But there’s a problem when administrators who are highly tuned to serving the needs of a suburban auto dominant landscape attempt to infill a more human scaled walkable environment. I shake my head when I see brand new improvements being installed in a manner that is out of touch with the intended use.

Yes, pedestrians and people in wheel chairs can wiggle around lamp posts and telephone poles plopped down repeatedly in the middle of the sidewalk. But why do this? Someone at the Department of Transportation in a remote office park went down a standard list. Concrete and brick pavers. Check. Decorative fake French light fixtures. Check. Minimum set back requirements. Check. But on the ground it doesn’t add up to a sensible whole. And this stuff is going to be stuck in place for decades.

Notice that not once was a pole placed in the center of a driveway curb cut or the middle of a freshly paved vehicular travel lane. Could cars slow down and drive around such obstacles? Sure. But engineers understand how ridiculous it would be to do that. The problem is that the folks who design and build pedestrian infrastructure never walk or bike themselves so these things never occur to them. So we’re left with this half assed obstacle course.

This piece originally appeared on Granola Shotgun.

John Sanphillippo lives in San Francisco and blogs about urbanism, adaptation, and resilience at granolashotgun.com. He's a member of the Congress for New Urbanism, films videos for faircompanies.com, and is a regular contributor to Strongtowns.org. He earns his living by buying, renovating, and renting undervalued properties in places that have good long term prospects. He is a graduate of Rutgers University.