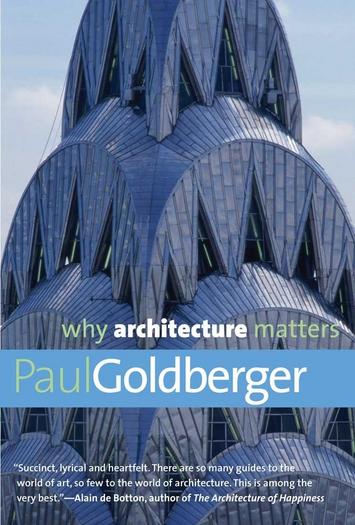

This jaded land, Florida, is the world-weary capital of architectural irony, with more tongue-in-cheek showpieces than even Las Vegas. But hidden within the MedRev McMansions, the stucco-smeared stage sets, and the high cynicism of our highway junkspace, there lies hidden a handful of true works of quiet beauty. Leave it to Paul Goldberger, Pulitzer prize-winning architecture critic and best-selling author of Why Architecture Matters, to point it out to us godless heathens. In an interview, he tells me that he’s excited to tour these nuggets we’re hoarding. Who knew?

“While Frank Lloyd Wright and other ‘star-chitects’ hogged center stage,” Goldberger says, “many more created earnest, sincere buildings that fulfilled their obligation to the street. These unsung heroes of American architecture matter. I think that James Gamble Rogers II was one of these in Winter Park. I hope so, anyway, because I’m coming down from New York to see them for the first time ever.” Sincere architecture: an endangered species in the world today, but in over-themed Orlando, practically nonexistent.

Last year, a popular vote placed Cinderella’s Castle in Florida’s top 100 most influential pieces of architecture. For God’s sake. At the same time Goldberger, the consummate modernist connoisseur, revealed his admiration for Yale University’s Gothic architecture, which he told me “belongs to a different age … it shows innocence risen to a heroic grandeur.” Speaking of its crusty stone structures as “deeply ethical,” Goldberger praised the buildings for their sincerity. Today this architectural authenticity has all but vanished among the fake Mediterranean, fake Colonial and fake just-about-everything, so it stands out when you see it.

Yale’s original campus was designed by James Gamble Rogers. He happened to have a nephew, James Gamble Rogers II, who was an architect in Winter Park and designed some of the most viscerally marvelous houses I’ve seen. 160 Glenridge Way, for example, is a shaggy, organic, simply gorgeous shingle-style cottage. Casa Feliz, one of his best, is modeled after an Andalusian farmhouse, standing today at the north end of swanky Park Avenue. Its humble brick and barrel tile have a prehistoric quality, as if a woolly mammoth had wandered into a cocktail party, snorkeling martinis. Its studied casualness is sophisticated and resonates with your deepest emotions, if you aren’t yet numb from Orlando’s overwrought garish glitz.

Goldberger seeks something real, the unadorned truth, in his voyage here next week. He says that he’s come to Orlando many times and enjoys “the theater of the theme parks,” and confesses he has yet to set foot in Winter Park. It may be the ultimate irony that Central Florida’s lure for the most important architecture critic of our time is a few humble, unadorned houses tucked into side streets, largely overlooked by the rest of us.

This piece first appeared at Orlando Weekly.

Richard Reep is an architect and artist who lives in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and he has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.