There is mounting concern in Australia about the nature and extent of country’s housing affordability crisis. Expressions of distress are not limited to the middle income households who are locked out of the Great Australian Dream of home ownership. There is heightened interest from advocates of low income households and an opposition political party. Moreover, Australia's overvalued housing is receiving renewed attention in international circles.

Part of this attention is attributable to the 7th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, which was released in late January. The Demographia Survey, which I co-author with Hugh Pavletich of Performance Urban Planning in Christchurch (New Zealand) covered 325 Metropolitan markets in seven nations (United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and Hong Kong, in China). The Survey assesses housing affordability using the United Nations and World Bank recommended measure of median house price divided by median household income (the Median Multiple). The data shows housing to be severely unaffordable in Australia, which was the most unaffordable nation included in the survey.

In response, Michael Perusco of Melbourne's Sacred Heart Mission and chairman of the Council to Homeless Persons called the affordability statistics "alarming.“ He added he was not surprised by the housing affordability data, noting the stress on the people he serves caused by inflated prices.

Kirsten Moore recently reported in these pages on the statement by the Australian Green party. Senator Scott Ludlam, the party's shadow minister (spokesperson) for housing called Australia's housing affordability a "world-class outrage." He went on to say "When a family or an individual has to spend so much of their income on paying their mortgage, it has a seriously adverse affect on their education and training opportunities, on their investment opportunities and on their ability to pay for services like health care and child care."

The real estate industry also expressed concern. David Airey, president of the Real Estate Industry Association of Australia issued a statement in response to the Demographia Survey, saying that: "for the majority of Australian families the difference between household income and loan payments is narrowing quickly."

Various measures indicate that households with mortgage payments equaling 30 to 35 percent or more of their gross annual income on mortgage suffer from “mortgage stress." Mortgage stress has been spreading around Australia like invasive species. Last year's Demographia Survey showed that the median income household in Sydney would pay 57 percent of its income for a mortgage if it bought a median priced house in the current market. In Adelaide, the figure would have been 47 percent. Over the last year things have only gotten worse.

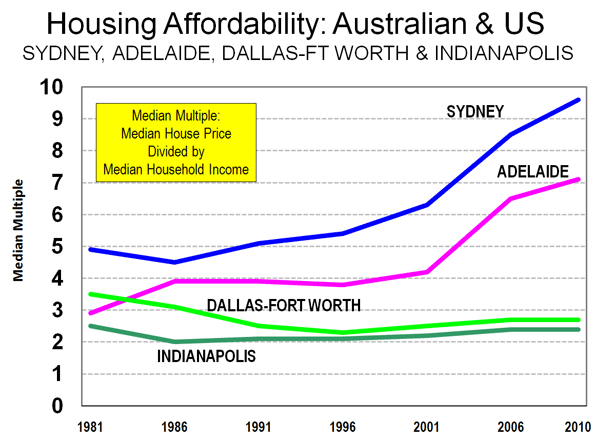

This is not merely a response to growth, or economic vitality. The median income household in the vibrant Dallas-Fort Worth region, for example, (larger than Sydney) would pay approximately 17 percent of their incomes for a mortgage on the median priced house. This is despite the fact that population growth and the demand for housing has been much greater in Dallas-Fort Worth than in Sydney (Figure 1).

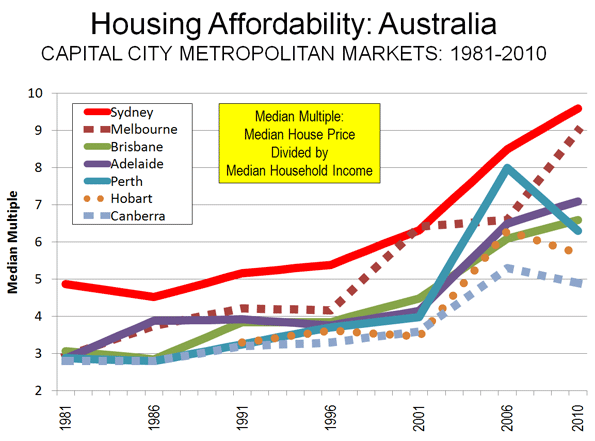

In Indianapolis, similarly sized to Adelaide and growing faster, the median income household would pay 14 percent of their income for a mortgage on the median priced house. House prices have risen more than 130 percent relative to incomes over the last three decades in Australia's major metropolitan areas (Figure 2). By comparison, the increase has been only one-eighth as much (16 percent) in the United States.

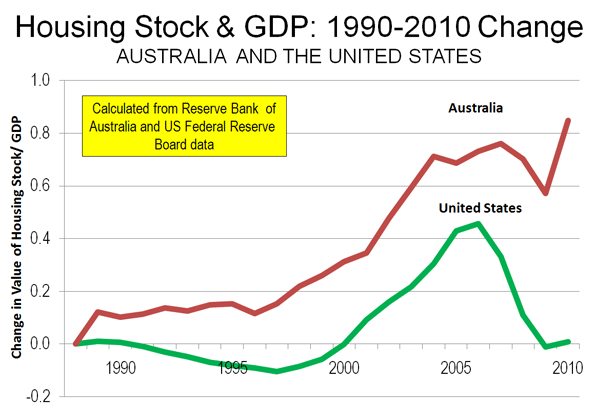

The extent of the house price increases is starkly illustrated by comparing the value of the own housing stock to the gross domestic products of Australia and the United States since 1988 (the first year for which Australian house value data is readily available).

According to data from the United States Federal Reserve Board, the value of the US stock of owned housing in 2010 was approximately the same in relation to the Gross Domestic Product as it was in 1990. On the other hand data from the Reserve Bank of Australia indicates that the value of the own housing stock in Australia was 85 percent higher relative to the Gross Domestic Product than in 1990. Thus, the value of the owned housing stock in Australia is today at least $1.9 trillion greater than it would have been if the 1990 ratio had been retained (Figure 3).

Of course, part, although far from all of the United States experienced a severe housing bubble that burst in 2007. Even so, the increase in gross house values relative to the gross domestic product in the United States never approached the massive increase in valuation that has occurred in Australia.

The Green Party statement rightly blamed "Government's actions that provide incentives designed to benefit investors and speculators and to keep house prices going up." The price rises have been principally the result of state government policies banning most development on the urban fringe and created a severe shortage of competitively priced land for development. It is an established economic fact of life that, all things being equal, the prices of goods and services tend to rise where there are serious limitations on supply, whether land, petroleum or bananas (as in the case of Typhoon Larry in Queensland in 2006).

The effects of such policies is to telegraph to investors both in Australia and around the world the potential for speculative gain in a housing market. The biggest losers come largely from the ranks of younger middle income Australians, including many immigrants, who would like to own their own homes. It is astounding that in egalitarian Australia, which has an enviable historic record of concern for lower and middle income households, is being transformed into a country where inheritance or access to foreign capital will be a prerequisite for home ownership for middle income people.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has raised concerns about the role of restrictive land use regulations in Australia (as well as the United Kingdom, which is also covered in the Demographia Survey). OECD has recommended that Australia ease land supply constraints by streamlining planning and zoning regulations.

The experience of Australia, along with a number of other markets covered in the Demographia Survey demonstrates that severe restrictions on the supply of land for development remain fundamentally incompatible with both housing affordability and the aspirations of lower and middle income citizens.

Photograph: New "detached" housing in Perth (by author).

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

No wonder why the wise men

No wonder why the wise men say that all you do in a lifetime, you definitely have to do it with patience. Statistics underline this in a very precise manner. The affordability rate goes down in a direct proportion to the expansion of the economical crisis. Furthermore, if it hadn`t been for the crisis which, by the way, reflects in all the society fields, there would still have been the so-called "growing pains" of the personal financial evolution. Me and my husband, we have been renting for a few years now, until we barely managed to obtain a bank loan and buy our own house. It has only been a year since we finally managed to arrange the house after our own tastes, decorating the backyard, repainting the walls in all rooms, changing the

Bathroom Vanities and the livingroom furniture. Each and every house accomodation improvement came slowly afterward, one small investment at a time.