Readers of this forum have probably heard rumors of gentrification in post-Katrina New Orleans. Residential shifts playing out in the Crescent City share many commonalities with those elsewhere, but also bear some distinctions and paradoxes. I offer these observations from the so-called Williamsburg of the South, a neighborhood called Bywater.

Gentrification arrived rather early to New Orleans, a generation before the term was coined. Writers and artists settled in the French Quarter in the 1920s and 1930s, drawn by the appeal of its expatriated Mediterranean atmosphere, not to mention its cheap rent, good food, and abundant alcohol despite Prohibition. Initial restorations of historic structures ensued, although it was not until after World War II that wealthier, educated newcomers began steadily supplanting working-class Sicilian and black Creole natives.

By the 1970s, the French Quarter was largely gentrified, and the process continued downriver into the adjacent Faubourg Marigny (a historical moniker revived by Francophile preservationists and savvy real estate agents) and upriver into the Lower Garden District (also a new toponym: gentrification has a vocabulary as well as a geography). It progressed through the 1980s-2000s but only modestly, slowed by the city’s abundant social problems and limited economic opportunity. New Orleans in this era ranked as the Sun Belt’s premier shrinking city, losing 170,000 residents between 1960 and 2005. The relatively few newcomers tended to be gentrifiers, and gentrifiers today are overwhelmingly transplants. I, for example, am both, and I use the terms interchangeably in this piece.

One Storm, Two Waves

Everything changed after August-September 2005, when the Hurricane Katrina deluge, amid all the tragedy, unexpectedly positioned New Orleans as a cause célèbre for a generation of idealistic millennials. A few thousand urbanists, environmentalists, and social workers—we called them “the brain gain;” they called themselves YURPS, or Young Urban Rebuilding Professionals—took leave from their graduate studies and nascent careers and headed South to be a part of something important.

Many landed positions in planning and recovery efforts, or in an alphabet soup of new nonprofits; some parlayed their experiences into Ph.D. dissertations, many of which are coming out now in book form. This cohort, which I estimate in the low- to mid-four digits, largely moved on around 2008-2009, as recovery moneys petered out. Then a second wave began arriving, enticed by the relatively robust regional economy compared to the rest of the nation. These newcomers were greater in number (I estimate 15,000-20,000 and continuing), more specially skilled, and serious about planting domestic and economic roots here. Some today are new-media entrepreneurs; others work with Teach for America or within the highly charter-ized public school system (infused recently with a billion federal dollars), or in the booming tax-incentivized Louisiana film industry and other cultural-economy niches.

Brushing shoulders with them are a fair number of newly arrived artists, musicians, and creative types who turned their backs on the Great Recession woes and resettled in what they perceived to be an undiscovered bohemia in the lower faubourgs of New Orleans—just as their predecessors did in the French Quarter 80 years prior. It is primarily these second-wave transplants who have accelerated gentrification patterns.

Spatial and Social Structure of New Orleans Gentrification

Gentrification in New Orleans is spatially regularized and predictable. Two underlying geographies must be in place before better-educated, more-moneyed transplants start to move into neighborhoods of working-class natives. First, the area must be historic. Most people who opt to move to New Orleans envision living in Creole quaintness or Classical splendor amidst nineteen-century cityscapes; they are not seeking mundane ranch houses or split-levels in subdivisions. That distinctive housing stock exists only in about half of New Orleans proper and one-quarter of the conurbation, mostly upon the higher terrain closer to the Mississippi River. The second factor is physical proximity to a neighborhood that has already gentrified, or that never economically declined in the first place, like the Garden District.

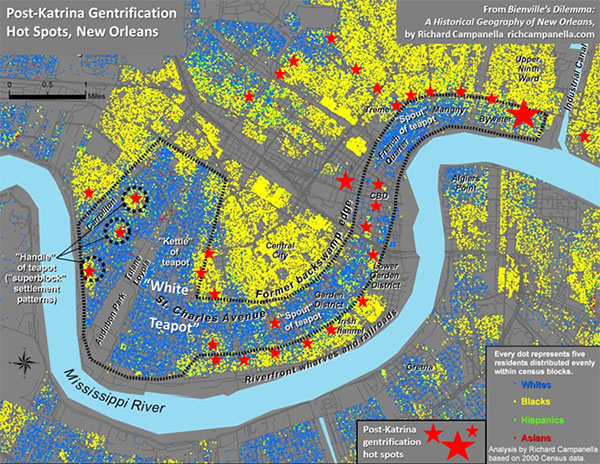

Gentrification hot-spots today may be found along the fringes of what I have (somewhat jokingly) dubbed the “white teapot,” a relatively wealthy and well-educated majority-white area shaped like a kettle (see Figure 1) in uptown New Orleans, around Audubon Park and Tulane and Loyola universities, with a curving spout along the St. Charles Avenue/Magazine Street corridor through the French Quarter and into the Faubourg Marigny and Bywater. Comparing 2000 to 2010 census data, the teapot has broadened and internally whitened, and the changes mostly involve gentrification. The process has also progressed into the Faubourg Tremé (not coincidentally the subject of the HBO drama Tremé) and up Esplanade Avenue into Mid-City, which ranks just behind Bywater as a favored spot for post-Katrina transplants. All these areas were originally urbanized on higher terrain before 1900, all have historic housing stock, and all are coterminous to some degree.

Figure 1. Hot spots (marked with red stars) of post-Katrina gentrification in New Orleans, shown with circa-2000 demographic data and a delineation of the “white teapot.” Bywater appears at right. Map and analysis by Richard Campanella.

The frontiers of gentrification are “pioneered” by certain social cohorts who settle sequentially, usually over a period of five to twenty years. The four-phase cycle often begins with—forgive my tongue-in-cheek use of vernacular stereotypes: (1) “gutter punks” (their term), young transients with troubled backgrounds who bitterly reject societal norms and settle, squatter-like, in the roughest neighborhoods bordering bohemian or tourist districts, where they busk or beg in tattered attire.

On their unshod heels come (2) hipsters, who, also fixated upon dissing the mainstream but better educated and obsessively self-aware, see these punk-infused neighborhoods as bastions of coolness.

Their presence generates a certain funky vibe that appeals to the third phase of the gentrification sequence: (3) “bourgeois bohemians,” to use David Brooks’ term. Free-spirited but well-educated and willing to strike a bargain with middle-class normalcy, this group is skillfully employed, buys old houses and lovingly restores them, engages tirelessly in civic affairs, and can reliably be found at the Saturday morning farmers’ market. Usually childless, they often convert doubles to singles, which removes rentable housing stock from the neighborhood even as property values rise and lower-class renters find themselves priced out their own neighborhoods. (Gentrification in New Orleans tends to be more house-based than in northeastern cities, where renovated industrial or commercial buildings dominate the transformation).

After the area attains full-blown “revived” status, the final cohort arrives: (4) bona fide gentry, including lawyers, doctors, moneyed retirees, and alpha-professionals from places like Manhattan or San Francisco. Real estate agents and developers are involved at every phase transition, sometimes leading, sometimes following, always profiting.

Native tenants fare the worst in the process, often finding themselves unable to afford the rising rent and facing eviction. Those who own, however, might experience a windfall, their abodes now worth ten to fifty times more than their grandparents paid. Of the four-phase process, a neighborhood like St. Roch is currently between phases 1 and 2; the Irish Channel is 3-to-4 in the blocks closer to Magazine and 2-to-3 closer to Tchoupitoulas; Bywater is swiftly moving from 2 to 3 to 4; Marigny is nearing 4; and the French Quarter is post-4.

Locavores in a Kiddie Wilderness

Tensions abound among the four cohorts. The phase-1 and -2 folks openly regret their role in paving the way for phases 3 and 4, and see themselves as sharing the victimhood of their mostly black working-class renter neighbors. Skeptical of proposed amenities such as riverfront parks or the removal of an elevated expressway, they fear such “improvements” may foretell further rent hikes and threaten their claim to edgy urban authenticity. They decry phase-3 and -4 folks through “Die Yuppie Scum” graffiti, or via pasted denunciations of Pres Kabacoff (see Figure 2), a local developer specializing in historic restoration and mixed-income public housing.

Phase-3 and -4 folks, meanwhile, look askance at the hipsters and the gutter punks, but otherwise wax ambivalent about gentrification and its effect on deep-rooted mostly African-American natives. They lament their role in ousting the very vessels of localism they came to savor, but also take pride in their spirited civic engagement and rescue of architectural treasures.

Gentrifiers seem to stew in irreconcilable philosophical disequilibrium. Fortunately, they’ve created plenty of nice spaces to stew in. Bywater in the past few years has seen the opening of nearly ten retro-chic foodie/locavore-type restaurants, two new art-loft colonies, guerrilla galleries and performance spaces on grungy St. Claude Avenue, a “healing center” affiliated with Kabacoff and his Maine-born voodoo-priestess partner, yoga studios, a vinyl records store, and a smattering of coffee shops where one can overhear conversations about bioswales, tactical urbanism, the klezmer music scene, and every conceivable permutation of “sustainability” and “resilience.”

It’s increasingly like living in a city of graduate students. Nothing wrong with that—except, what happens when they, well, graduate? Will a subsequent wave take their place? Or will the neighborhood be too pricey by then?

Bywater’s elders, families, and inter-generational households, meanwhile, have gone from the norm to the exception. Racially, the black population, which tended to be highly family-based, declined by 64 percent between 2000 and 2010, while the white population increased by 22 percent, regaining the majority status it had prior to the white flight of the 1960s-1970s. It was the Katrina disruption and the accompanying closure of schools that initially drove out the mostly black households with children, more so than gentrification per se.1 Bywater ever since has become a kiddie wilderness; the 968 youngsters who lived here in 2000 numbered only 285 in 2010. When our son was born in 2012, he was the very first post-Katrina birth on our street, the sole child on a block that had eleven when we first arrived (as category-3 types, I suppose, sans the “bohemian”) from Mississippi in 2000.2

Impact on New Orleans Culture

Many predicted that the 2005 deluge would wash away New Orleans’ sui generis character. Paradoxically, post-Katrina gentrifiers are simultaneously distinguishing and homogenizing local culture vis-à-vis American norms, depending on how one defines culture. By the humanist’s notion, the newcomers are actually breathing new life into local customs and traditions. Transplants arrive endeavoring to be a part of the epic adventure of living here; thus, through the process of self-selection, they tend to be Orleaneophilic “super-natives.” They embrace Mardi Gras enthusiastically, going so far as to form their own krewes and walking clubs (though always with irony, winking in gentle mockery at old-line uptown krewes). They celebrate the city’s culinary legacy, though their tastes generally run away from fried okra and toward “house-made beet ravioli w/ goat cheese ricotta mint stuffing” (I’m citing a chalkboard menu at a new Bywater restaurant, revealingly named Suis Generis, “Fine Dining for the People;” see Figure 2). And they are universally enamored with local music and public festivity, to the point of enrolling in second-line dancing classes and taking it upon themselves to organize jazz funerals whenever a local icon dies.

By the anthropologist’s notion, however, transplants are definitely changing New Orleans culture. They are much more secular, less fertile, more liberal, and less parochial than native-born New Orleanians. They see local conservatism as a problem calling for enlightenment rather than an opinion to be respected, and view the importation of national and global values as imperative to a sustainable and equitable recovery. Indeed, the entire scene in the new Bywater eateries—from the artisanal food on the menus to the statement art on the walls to the progressive worldview of the patrons—can be picked up and dropped seamlessly into Austin, Burlington, Portland, or Brooklyn.

Figure 2. “Fine Dining for the People:” streetscapes of gentrification in Bywater. Montage by Richard Campanella.

A Precedent and a Hobgoblin

How will this all play out? History offers a precedent. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, better-educated English-speaking Anglos moved in large numbers into the parochial, mostly Catholic and Francophone Creole society of New Orleans. “The Americans [are] swarming in from the northern states,” lamented one departing French official, “invading Louisiana as the holy tribes invaded the land of Canaan, [each turning] over in his mind a little plan of speculation”—sentiments that might echo those of displaced natives today.3 What resulted from the Creole/Anglo intermingling was not gentrification—the two groups lived separately—but rather a complex, gradual cultural hybridization. Native Creoles and Anglo transplants intermarried, blended their legal systems, their architectural tastes and surveying methods, their civic traditions and foodways, and to some degree their languages. What resulted was the fascinating mélange that is modern-day Louisiana.

Gentrifier culture is already hybridizing with native ways; post-Katrina transplants are opening restaurants, writing books, starting businesses and hiring natives, organizing festivals, and even running for public office, all the while introducing external ideas into local canon. What differs in the analogy is the fact that the nineteenth-century newcomers planted familial roots here and spawned multiple subsequent generations, each bringing new vitality to the city. Gentrifiers, on the other hand, usually have very low birth rates, and those few that do become parents oftentimes find themselves reluctantly departing the very inner-city neighborhoods they helped revive, for want of playmates and decent schools. By that time, exorbitant real estate precludes the next wave of dynamic twenty-somethings from moving in, and the same neighborhood that once flourished gradually grows gray, empty, and frozen in historically renovated time. Unless gentrified neighborhoods make themselves into affordable and agreeable places to raise and educate the next generation, they will morph into dour historical theme parks with price tags only aging one-percenters can afford.

Lack of age diversity and a paucity of “kiddie capital”—good local schools, playmates next door, child-friendly services—are the hobgoblins of gentrification in a historically familial city like New Orleans. Yet their impacts seem to be lost on many gentrifiers. Some earthy contingents even expresses mock disgust at the sight of baby carriages—the height of uncool—not realizing that the infant inside might represent the neighborhood’s best hope of remaining down-to-earth.

Need evidence of those impacts? Take a walk on a sunny Saturday through the lower French Quarter, the residential section of New Orleans’ original gentrified neighborhood. You will see spectacular architecture, dazzling cast-iron filigree, flowering gardens—and hardly a resident in sight, much less the next generation playing in the streets. Many of the antebellum townhouses have been subdivided into pied-à-terre condominiums vacant most of the year; others are home to peripatetic professionals or aging couples living in guarded privacy behind bolted-shut French doors. The historic streetscapes bear a museum-like stillness that would be eerie if they weren’t so beautiful.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Geographies of New Orleans, Delta Urbanism, Lincoln in New Orleans, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, and nolacampanella on Twitter.

--------

1 The years-long displacement opened up time and space for the ensuing racial and socio-economic transformations to gain momentum, which thence increased housing prices and impeded working-class households with families from resettling, or settling anew.

2 These Census Bureau race and age figures are drawn from what most residents perceive to be the main section of Bywater, from St. Claude Avenue to the Mississippi River, and from Press Street to the Industrial Canal. Other definitions of neighborhood boundaries exist, and needless to say, each would yield differing statistics.

3 Pierre Clément de Laussat, Memoirs of My Life (Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge and New Orleans, 1978 translation of 1831 memoir), 103.

Gentrification

I respect Richard immensely, but I have a problem describing as "gentrification" middle-class white people moving back to neighborhoods that were initially settled by middle-class white and black people, but that became slums after white flight in the 1970s. To me, that is recovery, plain and simple.

Furthermore, if people buy grand mansions built by successful merchants - that were later turned into crappy apartments - and renovate them as mansions, is that gentrification? I think not. I don't care HOW LONG these properties were serving poor populations as inadequate housing, they are being returned to their intended purpose.

Treme was traditionally settled by working class craftsmen who built their own homes. There, I can see an argument for gentrification. But certainly in Mid-City and the LGD - and possibly in the Marigny, Bywater and other areas, the people who own these homes now are comparable with those who built them originally. They enjoy many of the same pursuits. The fact that our tastes are now more sophisticated and we eat goat cheese versus Creole cream cheese is a sign of the times and a product of modern life, not gentrification.

For that matter, I don't see how you can argue that the French Quarter has been overly gentrified, given that the people who originally settled it were successful business people or wealthy landowners, in many cases.

The rise and fall of New Orleans' fortunes has been too significant and frequent for most neighborhoods to qualify as "gentrified."

I submit that the entire cadre of "urban community saviors" needs to focus on the history of the neighborhood and stop calling "gentrification" what is clearly urban recovery and preservation.

This is linear metamorphosis, not "recovery" of a past state

Your point is interesting; however, the past where most of the population lived in the urban core has no resemblance to the modern day "recovery", which really is gentrification. The urban core has morphed completely from what it once was.

The "flight" phenomenon is not so much "white" as "upwardly mobile". It is an economic phenomenon rather than a racial one. Any minority member who could afford to, fled too. They have "white trash" or "Chavs" making up the majority of the population in some blighted areas of cities in the UK; and anyone who can, gets out, including once-poor Asians who work harder and are more thrifty.

I know there is a paper somewhere which finds that cities that retained "industry" in their cores for the longest, lost the MOST residents. A higher rate of industries moving out of the core actually correlates to earlier metamorphosis to "gentrified" conditions.

One of the curious features

One of the curious features of the so-called "urban renewal" taking place in the United States is the insistence of two new master-signifiers: gentrification and sustainability.

In Paris, where I have lived for the last nine years, neither of these terms has imposed itself on general discourse as they have in the United States. Although the process of gentrification exists, it does not capture the imagination of those who witness, participate in, or are displaced because of it. It would appear that in France, "gentrification" is considered an inevitable feature of the ebb and flow of city life. Likewise with "sustainability", which is not seen as a magical master-signifier leading the way forward towards the perfect form of social organization, but rather as something that is simply preferable to its alternatives. In other words, these two concepts, although they exist in France and in French, have not inspired the same fetishization that they have in the United States.

Let us first address the question of gentrification. Gentrification, as explored, for example, in Richard Campanella's article on the post-Katrina metamorphosis of New Orleans, refers to the irruption of a new form of social organization. We must not, however, content ourselves with a simple description of the process by which succeeding demographic waves transform a city from, essentially, poor and black to rich and white. We must rather focus our attention on the new meta-phenomenon of the fascination with this process on the part of those who are its agents.

Cities change. Rich areas go to seed. Poor areas get rich again. Such is the cycle of city life. What is happening now is different. If so many people are interested in gentrification as such, if this process suddenly needs a word, it is because this word refers to what might be referred to as a symptom in all of its dignity and not simply a background peristaltic process. Speaking broadly, what distinguishes a symptom from a simple conflict is that the symptom incarnates the dialectical process as such. Like the eye of the storm on Jupiter that roams across the surface of the planet without ever resolving itself, the symptom is that nodal point in the dialectical process where the irreducible ontological kernel of conflict manifests itself.

Of what, then, is gentrification a symptom? Gentrification is a symptom of the passage from the social form of a World proper to the form of a non-world. A world is a consistent society ruled by a differential symbolic logic in which every member of the society occupies a fixed place in relation to the "au-moins-un" father at the center, who embodies and quarantines Difference as such. A world is a legible whole with a specific shape. A non-world has no shape, is a refusal of shape as such.

Gentrification has thus gone from a banal process to an object of fascination because we sense that there is something irreversible and properly Historical about what is happening to cities today. It is not just that poor areas are become rich; it is nothing less than a particular relationship with the Real that is being lost.

Let us allow Campanella to describe the process:

"The frontiers of gentrification are “pioneered” by certain social cohorts who settle sequentially, usually over a period of five to twenty years. The four-phase cycle often begins with—forgive my tongue-in-cheek use of vernacular stereotypes: (1) “gutter punks” (their term), young transients with troubled backgrounds who bitterly reject societal norms and settle, squatter-like, in the roughest neighborhoods bordering bohemian or tourist districts, where they busk or beg in tattered attire.

On their unshod heels come (2) hipsters, who, also fixated upon dissing the mainstream but better educated and obsessively self-aware, see these punk-infused neighborhoods as bastions of coolness.

Their presence generates a certain funky vibe that appeals to the third phase of the gentrification sequence: (3) “bourgeois bohemians,” to use David Brooks’ term. Free-spirited but well-educated and willing to strike a bargain with middle-class normalcy, this group is skillfully employed, buys old houses and lovingly restores them, engages tirelessly in civic affairs, and can reliably be found at the Saturday morning farmers’ market. Usually childless, they often convert doubles to singles, which removes rentable housing stock from the neighborhood even as property values rise and lower-class renters find themselves priced out their own neighborhoods. (...)

After the area attains full-blown “revived” status, the final cohort arrives: (4) bona fide gentry, including lawyers, doctors, moneyed retirees, and alpha-professionals from places like Manhattan or San Francisco. Real estate agents and developers are involved at every phase transition, sometimes leading, sometimes following, always profiting."

The Freudian technique consists in focusing on that which has been left out of the "official" story and recognizing it as the thread that, once pulled, unravels the official story as such and reveals something unexpected about the dialectical/analytical process.

Following this Freudian spirit, I would here like to turn away from a frontal analysis of gentrification and focus rather on what, at first glance, appears to be a contingent and secondary phenomenological detail of the gentrification process. Let us once again allow Campanella to speak:

LOCAVORES IN A KIDDIE WILDERNESS

(...)

Gentrifiers seem to stew in irreconcilable philosophical disequilibrium. Fortunately, they’ve created plenty of nice spaces to stew in. Bywater [a gentrifying neighborhood in New Orleans] in the past few years has seen the opening of nearly ten retro-chic foodie/locavore-type restaurants, two new art-loft colonies, guerrilla galleries and performance spaces on grungy St. Claude Avenue, a “healing center” (...) yoga studios, a vinyl records store, and a smattering of coffee shops where one can overhear conversations about bioswales, tactical urbanism, the klezmer music scene, and every conceivable permutation of “sustainability” and “resilience.”

(...)

They celebrate the city’s culinary legacy, though their tastes generally run away from fried okra and toward “house-made beet ravioli w/ goat cheese ricotta mint stuffing” (I’m citing a chalkboard menu at a new Bywater restaurant, revealingly named Suis Generis, “Fine Dining for the People”.

(...)

Indeed, the entire scene in the new Bywater eateries—from the artisanal food on the menus to the statement art on the walls to the progressive worldview of the patrons—can be picked up and dropped seamlessly into Austin, Burlington, Portland, or Brooklyn.

What I wish to highlight here is the strange way that food insists as a privileged symbol of the gentrifying process as such.

My thesis is that this is not a coincidence. It is a psychoanalytic commonplace to oppose orality to genitality. The former describes a regressive relationship to the object, one based on the infant's relationship with the maternal breast, in which the fact that the object is attached to a subject is repressed. The oral mode of interacting with the object, like the anal mode, is a mode in which the object is dirempted from the subject bearing it.

One of the lessons of Lacan's insight that the object is "extimate" is that subjectivity exists both inside and outside of us. Orality is a mode of relationship with the Other in which the denial of the Other's subjectivity goes hand in hand with a denial of one's own subjectivity. Genitality, the chimera of so many utopian post-Freudian schools, must nonetheless not be completely dismissed as a pure illusion. We must simply see it as another word for Becoming and not a fixed form of Being. Genitality might be considered a mode of relationship with the object in which its impossible resorption into the field of the Other is recognized. Is this not another way of distinguishing the jouissance of the symptom (organized around a fantasy of appropriating the object) from surplus-jouissance, which is generated by the circular motion around the object, one which thus presupposes its impossibility?

The "new" orality on display in the gentrified neighborhoods must be considered a manifestation of a radically different relationship with the object and with jouissance, one that illustrates the ideological constellation behind gentrification.

To return to one of the theses stated in our introduction, the non-world is a place in which difference is no longer coagulated into a Father but rather circulates and reproduces itself at the cellular level. Is this not another way of describing consumerism as opposed to previous forms of capitalism which might be described as "producerism"? A gentrified neighborhood is one that is organized around the consumption of jouissance, not the production of jouissance for the master. The nodal points of a world are those points at which jouissance is produced and laid at the feet of the master.

It is no coincidence either that the choicest sites for gentification are precisely those sites, like abandoned factories, which once served a production role and can now be turned into sites of consumption. The gentrification process is thus a process of cannibalization in which the remnants of the object, the leftover bones of the master, are consumed. In Totem and Taboo, Freud discusses the magical signification of consumption: by consuming the Father we acquire his strength; we literally put him inside of us. The gentrification process is thus something akin to the grinding up and eating of fossilized dinosaur bones in China: the remnants of a Real World in which there existed a Real Master are eaten because we have no other way of existing for the dead Master.

Once the confrontation with Difference has been endlessly deferred - in other words, once genitality, with its inevitable confrontation with the terrifying castration of the Other, has been refused -- jouissance can only be procured in a regressive, symptomatic mode that maintains the twin illusions that the uncastrated Other exists and that we can approach this Other without having to suffer castration ourselves.

Campanella highlights two other features of the gentrified non-world: first, that there are no children there, and second, that those who live there are fascinated with all forms of sustainability. These two clinical observations as well are connected.

First of all, the putative explanations for the obsession with sustainability (ecology, social justice), although perfectly plausible, must be dismissed as post hoc alibis that ignore the libidinal investment in this master-signifier. What is sustainability if not the dream of a post-sexual world? A "sustainable" ecosystem is one that reproduces itself perfectly and eternally without ever encountering an Other. A sustainable world is one in which reproduction takes place through parthenogenesis and not through sex, through a sexual confrontation with an Other who is, by definition, radically Different. No surprise, then, that a gentrified city is one in which there are no children!

The dream of sustainability is the dream of a life in which difference, by being ground up into tiny pieces, can be invisibly admixed to one's food and consumed like vitamins, in order that one may never have to realize that one is eating them. And what type of food do the gentrifiers eat? Campanella's subtitle, Locavores in a Kiddie Wilderness, says it all. They eat local food, preferably organic food, and here the gentrifiers show a certain degree of obsessionality in their global perversion: the ultimate fantasy behind eating local, organic food is the fantasy of reducing the cycle of eating and eliminating waste to its smallest possible circuit - in other words, the fantasy of eating one's own waste. As Levi-Strauss illustrates so beautifully in Tristes Tropiques, the fantasy here is fundamentally morbid and consists essentially in a refusal of existence on the concrete level, a refusal of the concrete as such. We might call this refusal to engage with the concreteness of existence by its more familiar name: puritanism, with its hidden coprophagic fantasies.

A scene that has begun recurring with more and more frequency recently, to the point where it has become a phenomenon worthy of being documented in the New York Times ("Restaurants Turn Camera-Shy", Helene Stapinksi, New York Times, January 22, 2013), might serve as an image of the particularly sterile form of sexual rapport typical of the non-world: a group of diners taking out their smartphones and photographing their meal before eating it. We see here the transformation of an already-pasteurized object of jouissance into an even less immediate object: a photograph. We have here an attempt to fuse with the object that is simultaneously an attempt to keep it at the greatest possible distance (which is a good way to render Lacan's paradoxical "il n'y a pas de rapport sexuel"). When we see someone photographing their food, we can imagine someone who first dissociates the breast from the (m)Other in order to pre-transform it into the fecal object that it will become in a few days (does not a plate of glistening curry photographed directly from above immediately evoke the perspective from which we contemplate the contents of the toilet bowl)? In this way the floating moment of subjectivization between ingestion and expulsion is negated before it can even occur. Finally, the isolated, fecalized breast is divorced from its very corporeality by reducing it to an abstract image that is then lodged in the Other of the blogosphere, where it can communicate with other blogs ("the signifier represents the subject for another signifier"). This is the way the residents of the non-world fuck.

Do we have a choice here? Is it possible for cities to evolve differently? No. Those who attempt to reinject some avatar of difference/authenticity into the process are what Lacan called non-dupes. This is the new world. The old signifiers of difference and authenticity no longer function as such once they are exposed to the logic of the non-world. The cunning of reason is implacable. They cannot be rehabilitated, and any attempt to do so only falls into its dialectical truth, that of simulacrum.

Let us rather try to enjoy our sexless organic brunch as much as we can and keep Heidegger's words in mind:

"Philosophy will not be able to effect an immediate transformation of the present condition of the world. This is not only true of philosophy, but of all merely human thought and endeavor. Only a god can save us. The sole possibility that is left for us is to prepare a sort of readiness, through thinking and poetizing, for the appearance of the god or for the absence of the god in the time of foundering; for in the face of the god who is absent, we founder."

www.timothylachin.com

Historical accident is fascinating

The great urban economist Alan W. Evans suggests that Paris and other European cities always did have the wealthiest people at the centre rather than the fringes, because that was the safest place in a siege - which Europe's history is rather fraught with. The cities also did tend to be built up more behind an inner defensive perimeter.

Very perceptive although I

Very perceptive although I have a problem with a few observations. Having lived through the gentrification process three times (and witnessing Williamsburg transform during frequent visits over several years) I have noticed an undeniable pattern, however, gutterpunks don't play a role. They will squat anywhere there is a vacant building near an active part of town. In my experience the vanguard has always been artists and service industry workers willing to risk a bad neighborhood for cheap rent.

Bywaters Gentrification

A Message To The Bywater from Sweden Beware of Letting The Privileged Write History And Define The Culture. Sweden is the high culture of gentrification. Here we are not even aloud to play on the street on many places, because of business interests and neighbors. Here its completely normal for a new neighbor to evict an orchestra that lived and flourished in an area for 30 years, just because "they annoy you". Happened to our sister orchestra recently, and Kiriaka can hardly find any place to practice in this town. In Bywater NOLA people Love us, but this town is infected by rich haters. So the message from Sweden; beware of letting the privileged write the history and define the culture.

Kiriaka

The letter above is from Kiriaka a Swedish troupe that participated in several non profit events and parades.

We are buskers Bunkhouse hosting musicians and artists from all over the world. One newcomer who we were glad to see aT first walks aroung wearing a B N A shirt as if it were a police uniform.

He complains if we talk to loud. Telling one couple who he could hear because the had their windo open.He said he could hear them and that he was a home owner and they were just renters they needed to quiet down.

I have had bands practicing there for years.My neighbors Loved it.He complained again and again and we quit.WE allways quit at ( but that wasn't early enought for him.We have to keep our voices down.

He has complained about all 3 houses around him. We are the majority and we must rule or loose to a bedroom community mentality. Join the B N A .There are members there now who agree.The silenced bands and others are

planning a Jazz Funeral for the Bywater The response has been great join us

MS Pearl

Buskers Bunkhouse

The ontological sciences

Ah...

Art, region, politics and NOLA- the ontological sciences...

Found all including the comments a great read-

And as a arrogant Yankee transplant of 20 years, it's fun to have tealeaves to read and see my DINK (dual- income- no kids)Wife and I get another classification.

Oscar Wilde said it best-

"there is no such thing as bad publicity"

So what if i'm turd burglin stage 3 butthead,

I have no regrets, and many ideas on how to end (or at least slow) the cycles of poverty that shoots first, asks questions later, and leaves us limped without toes trying to make 63 yard field goals.

White, right, or wrong- Richard Campanella's work is well worth reading.

Best From Freret,

Andy Brott

www.brottworks.com

p.s. my favorite nola explained quotes-

"NOLA is the land of Misfit Toys"

Thank you Sandy...

"Nola is a mirror- love it, and it loves you back- hate it, and it bites"

Thank you Grey Ghost...

and my all time favorite-

I love NOLA because I can't explain why I love NOLA...

AB

Original gentrifiers

I have two brief comments:

I think this article would be better served if 'gentrification,' as the author is using it, is clearly defined from the start.

I think it can not be more overstated that the reality of the situation is that for over 300 years New Orleans has occupied by non-natives and it began with Bienville. This country is only a country because of 'gentrification.'

A disappointing article

An example of taking a complex subject and simplifying it until it is no longer an accurate portrayal. Disappointing in someone as respected as the author. I lived in & have been familiar with the Bywater section of the city since long before it was commonly referred to by that name (except as a long forgotten area telephone exchange). It is evident that Richard Campanella does not know the area well enough to be writing about it.

an uninformed work...

Where to begin? This article is an ill-formed abortion. By an ill-informed man. I would sooner get more in depth and accurate detail from a third grader. What's my qualification? 32 states, 4 countries, 16 schools in 9 years. I smell where he is coming from and its a sad little place.

This was written by someone who doesn't analyze history. Who doesn't understand the gentrifications of the past (i.e. 1910 influenza, 1927, Betsy, etc) All of these events had a similar impact on the landscape. This is a continual process throughout time and this report has no grounding in a place in history, therefore its conclusions are the kind of stuff a Sigmund Freud would claim to be a successful hypothesis, with complete ignorance of control groups/events within the paradigm.

His errors are massive and ignorant of even local history (which is laughable since he purportedly lives here) Our first gentrification began with the "raw americans" in 1814 upon the sale to America. An entire side of town is known for this. Pretty glaring omission.

The quarter was not gentrified in the 1970's. Here, this fool could have found a clue in his new city as to the flight of Italian New Orleanians to Algiers and Metairie and points North in 1978, with New Orleans first black mayor. (be that what it may..) Throughout the 70s the Quarter was a de facto little Italy. In the 80s it was mostly what the CBD looks like now. That clue was the Italian Plaza.

In fact, the quarter was saved from having an i-310 put through it by the strong original community there in 1969.

Again... how bout a little actual research, guy?

Back to the earlier point, everything did not change after 2005. Changes that have been constant since 1814, 1865, 1910, 1927, 1965, continued. Clearly, this information has been omitted to attack a specific group (which annoy me as well) but this is a facile, juvenile, half-formed and misleading approach. Read Antigravity's expose on the food trucks if you want REAL reporting of this sort.

Caveat: as a former public school teacher, I HATE incomplete work and unsupported hypotheses.

additionally, there is a specific ignorance of economics in this article. I bought my house uptown for its flood plain affect. That is, there were great older houses in mid city which I liked, but where the price was lower, the water was higher, the insurance was triple. More often, people bought on the pre-1927 city plan (think what that date means) because the insurance and mortgages were together affordable. Add to that no security regarding the levees (including the fact that even later the ACE was STILL caught stuffing newspapers in levees.

This sounds like a guy who got here yesterday and lacks even the most basic 2005-2008 city infrastructure/operation knowledge.

and now, hm. the teapot. Omit your theory for the entire portion surrounding Audubon park for the entire existence of Tulane, Loyola, etc.. Omit your theory for the lower garden district for the entire history of its being from 1814 on.

As for the French Quarter, understand that the 90's condo boom is when that happened. Ask any musician over 50 what happened to jazz in the French Quarter.

So what do we have left? the Treme, the Marigny, the Bywater? and who are the culprits.

Gutterpunks? really? the brand new hobos of the 90s are the progenitors of gentrification?? This shows a real ignorance.

Study your architecture (here we go with your need for more research) and you will be enlightened). you have poor housing and poor neighborhoods. as immigrant or black as you might think.

you have immense houses, the purse string holders, you have factories.

As the manufacture moves away, the factories that don't crumble, become lofts, the Managers die off or move or fade and the large properties get chopped into apartments with 6 or 7 electric meters. So who moves into the poorer neighborhoods? Gay men and women. (by large, gay men).

There is nothing negative in this to me. Gay men see the value of the neighborhood and defend their own value against blanket judgements of character based on social stupidity. They befriend and respect my gay black students who deal with all of the homophobic bullshit in their own social community. They are, to me, a shining example of the value of 'be yourself. fuck em if they can't accept that.' (a value I hold dear).

as for the "gutterpunks" the researcher may not be aware that our tourist industry has ALWAYS operated on a mix of transients, immigrants and the poor. Welcome to the classist dichotomy. In fact, the Kentuckians who floated the bargeboard flats here, sold the wood for houses or built a house with it and integrated themselves into this city in much the same fashion (prior to 1850 that is).

as for the hipsters. do you fear them? this city has the power of temptation in the swamp. It will de-bone and devour a good number of them in so many ways. No matter WHAT you do, and every few years, (think of what I mean) this city will remind you of your safety obsession folly.

again with the poor economics. the beginning of the overpricing of a neighborhood starts with people from other cities paying higher rent, housing prices rising and the last of the renters moved on.

again...do some fucking research.

let me enlighten you: people were unable to return to this city because in October of 2005, in a city with LIMITED rental stock that would come back whenever -ever- it would...FEMA was paying workers $3000/month in rental stipends. Once the landlords heard about this, the rents went up and they NEVER went back down. I let one of them stay on my couch and she insisted on paying me money, which I refused, and then she let me in on what all of her friends and herself were getting paid in rental stipend.

also, another particular, gentrification in New Orleans is not house or loft based, it is avenue based. compare the size of the street in areas being renovated versus those less renovated. This is because of the "safety" factor involved in massive population depletions and the effect on restored city services. (think streetlights and crime)

The "phase of victimhood" segment ignores black professional migration and local history as migration (the lower 9th ward was a refuge for home desiring black WW2 vets who suffered the red lining tactics of New Orleans banks in the 40s and 50s.

You missed a much larger topic in your meanderings about how the more well-heeled enjoy the lower prices that vanish when what is essentially local slave labor goes away.

I understand your mystification at the jargon that is strung along with the occasional influx but you should have done comparative research, specifically with Magazine street in the 1990's vs now, but that would skew the assumptions you seem to have formed first, and then looked for conclusive connections as an afterthought. I'm going to bet that you live in the Bywater.

I know you claim to live here...but have you actually talked to ANYONE here?

In your pasting, you have ignored other key details. Southerner transplants vs Northerner. Small town vs. big city. Immigrant vs. resident.

It is ironic, that my wife, from here, the reason I am here (if she lived on mars I would pack a spacesuit) and a vegetarian, is well served by these kids coming here, no matter how silly their language or naming of things is. Our entire language here is a misunderstanding of some sort or another, assisted by the confusion of the English language

Americana, in which we mix and match Greek and Latin roots for a nice confusion (to wit: congress is the opposite of egress, NOT progress).

I think you may be confused about mardi gras in general. specifically the classism and cost of riding versus walking, of race and neighborhood. fuckall, I think you're confused about EVERYTHING.

I think in just about every place, your hypothesis falls apart. Regarding conservativism, I think of the local slumlords that paint everything beige for the arriving northerners and midwesterners, who arrive here wanting our Caribbean color scheme. You may be pinning the tail on the wrong donkey, son.

who do you think is the greater threat? naive kids who generally want to love this place and contribute something or some real estate developer asshole born and raised here, willing to sell their born and raised neighbor out for a quick buck? The fucking born and raised here Audubon street slumlord who owned my property had equally high rents through section 8, and not ONE appliance in place for his tenants. Not a fridge, not a stove, not a washer, not a dryer. One thing you fail to recognize, the lower numbered kids (in your scheme) actually can and do buy properties now and carry their values of acting equitably with them. I grew up homeless so...again...I know of that which I speak.

ah. finally, near the end of your "work" you stumble on to one of the influxes. Sorry, I responded in order. By the way, this means you contradicted yourself, which probably means you didn't plan this out and ran up against a deadline-especially since all of the other ideas in this piece are so ill-formed. I have a nose for that kind of bullshit. I was a school teacher.