By Joel Kotkin and Mark Schill

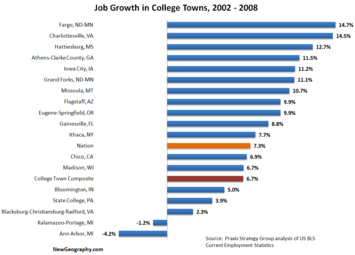

For much of their history college towns have been seen primarily as “pass through” communities servicing a young population that cycles in and out of the community. But more recently, certain college communities have grown into “knowledge-based” hot spots --- Raleigh-Durham, Madison, Cambridge and the area around Stanford University --- which have been able to not only retain some graduates but attract knowledge workers and investors from the rest of the country.

But a large proportion of college towns do not seem to be doing so well. For one thing, they often lack the historically high levels of aerospace and other technology investment --- and simply the scale --- that characterize the most successful university communities. Simply put, there are not enough large-scale high-tech opportunities to seed and sustain significant growth in most college towns.

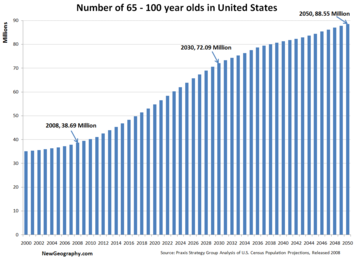

This does not mean there are not great opportunities for college communities to evolve in the next century. Many more possess the potential to become legitimate centers of technology, innovation, risk capital and cultural efflorescence. The key, we believe, is tapping the energies of the baby boomer generation. The baby boom generation far outnumbers its successor, Generation X, by roughly 76 million to 41 million. Due largely to boomers, by 2030 nearly one of five Americans will be over 65.

This does not mean there are not great opportunities for college communities to evolve in the next century. Many more possess the potential to become legitimate centers of technology, innovation, risk capital and cultural efflorescence. The key, we believe, is tapping the energies of the baby boomer generation. The baby boom generation far outnumbers its successor, Generation X, by roughly 76 million to 41 million. Due largely to boomers, by 2030 nearly one of five Americans will be over 65.

The ultimate locations chosen by those whom demographer Bill Frey calls “downshifting boomers” will be critical in terms of new residential and commercial development. This will be particularly true for college towns once the current “echo” generation --- currently 15 to 25 --- grows into adulthood and leaves college for other destinations.

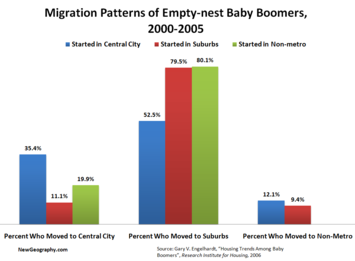

To understand the opportunity, we have to see the real situation of boomers. Despite the hype about a massive “back to the city” movement by aging boomers, this is a very small phenomenon, restricted largely to a small, usually highly affluent sub-set. Generally speaking, the further over the age of 35, the greater the chance an individual has of living in the suburbs or exurbs. Far more seniors, in fact, migrate from city to suburb than the other way around. It appears that a handful of relatively wealthy older suburbanites do establish residences in some inner-city locations, but overall the prime destination for those who move is the suburbs.

Recent research by Gary Engelhardt found that if central city dwelling boomers without kids moved, only 35 percent would remain in a central city region. Of those moving from a suburban home, just more than 11 percent decided to move into the central city.

Recent research by Gary Engelhardt found that if central city dwelling boomers without kids moved, only 35 percent would remain in a central city region. Of those moving from a suburban home, just more than 11 percent decided to move into the central city.

The most critical factor is the boomers’ tendency to “age in place,” at least until they become too old to care for themselves. Roughly three-quarters of retirees in the first block of boomers, according to Sandi Rosenbloom, a professor of urban planning and gerontology at the University of Arizona, appear to be sticking pretty close to the suburbs, where the vast majority reside. Those who do migrate, her studies suggests, tend to head farther out into the suburban periphery, not back towards the old downtown. Most continue to use single-occu¬pancy vehicles; few rely on public transit.

The reasons vary, Rosenbloom suggests, and include job commitments or the desire, as they age, to live close to and spend more time with children or grandchildren. Perhaps most importantly, the majority of boomers have spent most of their lives in sub-urban settings. They are, for the most part, not acculturated to the density, congestion and noise of inner city life.

Yet if they are not heading en masse to the inner city, Rosenbloom and other experts see a significant proportion heading to smaller towns. Many of the areas with the fastest growth in senior populations are already on the outward fringes of the metropolitan areas, but also in some of the more remote areas of country, including parts of the Rocky Mountains, the Sierra Nevada, and even Alaska. Indeed by 2030 Montana and Wyoming are expected to have among the highest percentage of seniors in the country.

Compared to most metropolitan areas smaller towns --- including college communities in places like the Great Plains, the South and interior California --- have remained remarkably affordable, and should continue to be so. Many baby-boomers may eventually consider an “equity migration” from the coasts. These households can enjoy a significant capital gain, and achieve a large reduction in debt, while still engaging in economic activities made possible by the Internet. [see Figure 2]

Compared to most metropolitan areas smaller towns --- including college communities in places like the Great Plains, the South and interior California --- have remained remarkably affordable, and should continue to be so. Many baby-boomers may eventually consider an “equity migration” from the coasts. These households can enjoy a significant capital gain, and achieve a large reduction in debt, while still engaging in economic activities made possible by the Internet. [see Figure 2]

As a rule, small town residents pay less of their income for housing than those in metropolitan areas, even though their incomes tend to be less. In 2003, even before the peak of the current housing boom, roughly 15 percent of all metropolitan households spent over half their income on housing while only 10 percent of those in non-metro areas suffered this same level of burden.

Quality of life considerations also could play a critical role in attracting newcomers to college towns, both in terms of cultural institutions and providing walk-able communities. College towns can also offer “continuing education” opportunities for an economically active population, many of whom plan to remain engaged in the economy well into their 60s and 70s. They can become a source of useful expertise as well as capital for those recent graduates who seek to start or expand local companies.

Colleges could maximize their real estate and financial position if they can bring in boomers as full or part-time residents. This is true not only in metropolitan areas but in broad parts of the country including the rural south, Midwest and places like Pennsylvania. Many boomers do not view retirement as a permanent vacation but as a place to start a “second life.” In many case they are turning to nontraditional and less expensive retirement spots.

Colleges could maximize their real estate and financial position if they can bring in boomers as full or part-time residents. This is true not only in metropolitan areas but in broad parts of the country including the rural south, Midwest and places like Pennsylvania. Many boomers do not view retirement as a permanent vacation but as a place to start a “second life.” In many case they are turning to nontraditional and less expensive retirement spots.

Successful college towns will connect with both the well educated, increasingly well connected younger workers already in town and the downshifting experienced professionals looking to balance livability with more urban amenities. Combined with well-educated boomers, this could create a powerful labor and knowledge base.

Done correctly, in accordance with a sound economic strategy, many college communities could find a new way to prosper and thrive in the years until 2020 during which the number of potential students is likely to drop. It may also provide some protection against other forces that threaten college growth, notably the increase in on-line classes, private colleges with numerous satellite locations and the growing problems with student debt.

Given these factors, college towns need to be reinvented in order to thrive in emerging environment. Most importantly, they must learn to take advantage of emerging demographic trends, particularly by taking advantage of the energies of an increasingly vital aging population.

Joel Kotin is Executive Editor of NewGeography.com. Mark Schill is Managing Editor and a community strategy consultant with Praxis Strategy Group.

I live in stony brook new

I live in stony brook new york right near the university and it is a perfect example of a college town i used to visit friends in Albany as well as at skidmore university which was my favorite college town by far. I remember seeing a fake degree from stony brook on some site thinking who in their right mind would try and put one off from that school which is in the top 60 in the country.